Lesson Study 1: Sixth Grade Book Genres

Content:

Throughout the year my sixth grade Language Arts class is introduced to different genres of books so that they can practice how to best read the material for comprehension and overall enjoyment. By the end of the year, the goal is for each student to read at least one book from the different genres discussed. This introductory lesson is meant to familiarize the students with the concept of literary genre as well as facilitate a discussion about how to categorize books into specific categories based on the book’s content. Take note, this lesson is meant to span over two or three days so the students will be able to really solidify their understanding of genre as a concept and a tool to use throughout the school year.

Process:

Students are accustomed to completing a daily warm up in their composition notebooks each day. Today the warm up will be more open- ended in that students will be asked to give their opinion. The question they must answer will probably go something like this:

What makes a book interesting to you? What are your favorite parts of this interesting book? Take the next five minutes to list as many different reasons as you can for why you like this book. You don’t have to write in complete sentences.

After a short while, I will ask the students to share their opinions with their table groups on what the word ‘genre’ means and how the students’ descriptor words that they came up with in their warm up might help put books into different subject categories.

After the students are done sharing within their table groups, I will hand out a quick little handout that gives a brief overview of the different components of each genre. The handout will provide an overarching definition of genre at the top and list the various other types of genres. The students will be able to use this as a guide in case they forget a particular genre throughout the school year. I will choose random students to read through the genre definitions at this time.

But wait! There’s more! The students will then be given a task to create a poster for around the room. They will create these in a group and will be assigned one particular genre from a list of genres at random. Using the given definition and their own brainstorms from their warm up, the students will be asked to create a poster that describes their particular genre. They will be given magazines, markers, glue, and whatever craft supplies their hearts’ desire to create a poster that gives examples of the genre along with key words associated with the genre. This will take some time to accomplish but once the posters are finished the students will be hang them up around the room. The posters will be a visual guide for the students so that they can quickly recognize different parts of different genres. The groups will then share their genres with the whole class and essentially ‘teach’ their peers all about their genre and the key words associated with the genre as well as give some examples from their poster.

Product:

The students will have a produced a poster that shows their understanding of their particular genre. Because this is a pretty lengthy introductory lesson, the overall goal is to connect students’ own understanding of a particular genre with terms and examples they already know. The students should be given an opportunity to create their own idea of what a particular genre entails by using words and images that they understand. The idea is to create a foundation in which the students are asked to make their own connections to that is relevant and useful to them in the future.

Evaluation:

At the end of the first day of this lesson, I will assign the students to write a one page reflection in their composition notebooks about genre for homework. This reflection will ask the students to pick their favorite genre and explain why it is they like that particular genre using the key words and images they talked about in class. The students will also include their least favorite genre and why they don’t like it/ have trouble with it. Their reflection should include insight as to how the student can use genres as reading tools for categorization in Language Arts. This is somewhat informal in that I will use these to judge the lesson plans and provide the supports needed to the students who have difficulty understanding different categories of genres. The more formal evaluation will be the poster which will be grade mostly on content and originality as opposed to presentation and style.

What kinds of thinking will the students need to do to participate in the lesson?

Overall the students will need to:

- Know the content

- Differentiate or comprehend the differences between different genres

- Create a visual aid that explains the particular genre using students’ own key words and phrases

- Reflect on their own opinions and preferences about genres and how they can use genre as a reading tool in Language Arts

To what extent do the students have options or choices regarding these lesson components?

While I must provide the lesson materials, the students autonomy really boils down to the creation of their posters and the discussions they lead within their table groups. The group discussion is essential to creating an understanding between peers. Not only will discussion facilitate cooperation, but also give kids to share their different insights and concerns about the concept. The lesson is structured, but is also give the kids a chance to create a tool that will best suit them in understanding the content.

Reflection:

When I first set out to create this lesson plan I had an idea about how I wanted to incorporate more student autonomy into the process and finished product. What came out of my lesson was a snarling monster of note-taking and fill-in-the- blank that would have stifled my students’ creativity and essentially smashed any dreams of them owning their own education. So I did what felt right, and I deleted that lesson study. I threw it out, emptied my virtual trash can, and never looked back. Lesson #1 learned from our peer editing class was something simple and yet crucial to being effective and engaging in the classroom: Throw things out. Start over. Invent that new wheel. And if your lesson plans turn into yet another snarling monster that needs to be tamed, you fight it head on and start over. Your kids will thank you one day for saving them from the burden of a lesson plan that didn’t require their special talents in defeating a particularly hard concept.

Lesson #2 learned through the peer evaluation process required the lesson plans to be tamed rather than slain. The valuable information that I received from my two peer reviewers helped me to see the flaws I was dealing with in my lesson plan. The information may have been there, the delivery and student participation were minimal at best. Thanks to my two evaluators, I was able to take a step back and see how the lesson was relevant to my students. Were they making their own choices? Were they being allowed to use what they already know and construct their own ideas about the concepts learned? Were they allowed to interact with peers during the lesson? It’s these sorts of questions that I should have been answering in my first set of failed lesson plans and the same questions that I hoped to address in my second, improved lesson plan.

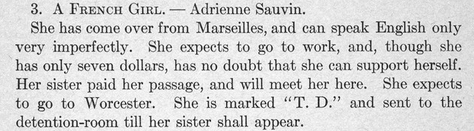

Photo title: Rural Wales needs £16,000,000

Photographer: Geoff Charles (1909-2002)

Accessed: Europeana Libraries Project