11th or 12th Grade Social Studies

This lesson would be well situated inside of a larger Imperialism unit. It may be used as either an illustrative case study or an in-depth exploration of the Americas at the time of the conquest.

Requisite Knowledge:

- Introductory knowledge of Spanish conquest of Central America under Cortéz

- Introductory knowledge of Aztec history and culture

- Introductory knowledge of Purépecha history and culture

Learning Targets:

- Sourcing

- Contextualization

Learning Segment Goal:

Students will apply their knowledge of the current cultural diffusion of Aztec values in modern societies to the historical record. In doing so, they will ask the question, how did the Aztec’s come to be remembered whereas another great society – the Purépecha of Michoacán – did not? Furthermore, are there any clues in primary sources created at the time of the conquest that suggest a possible reason?

Suggested Instructional strategies and learning tasks:

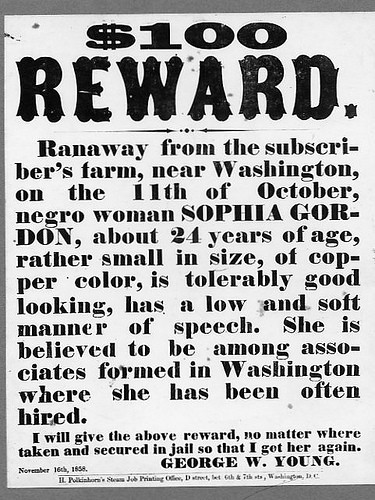

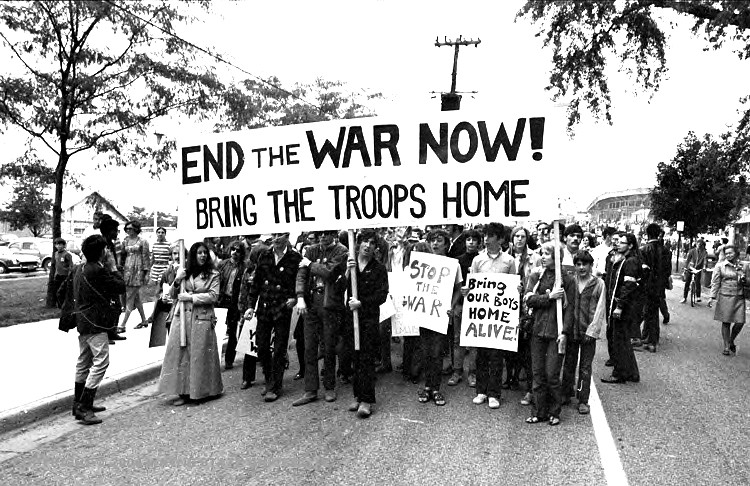

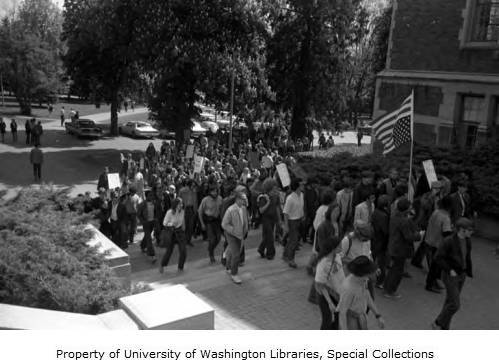

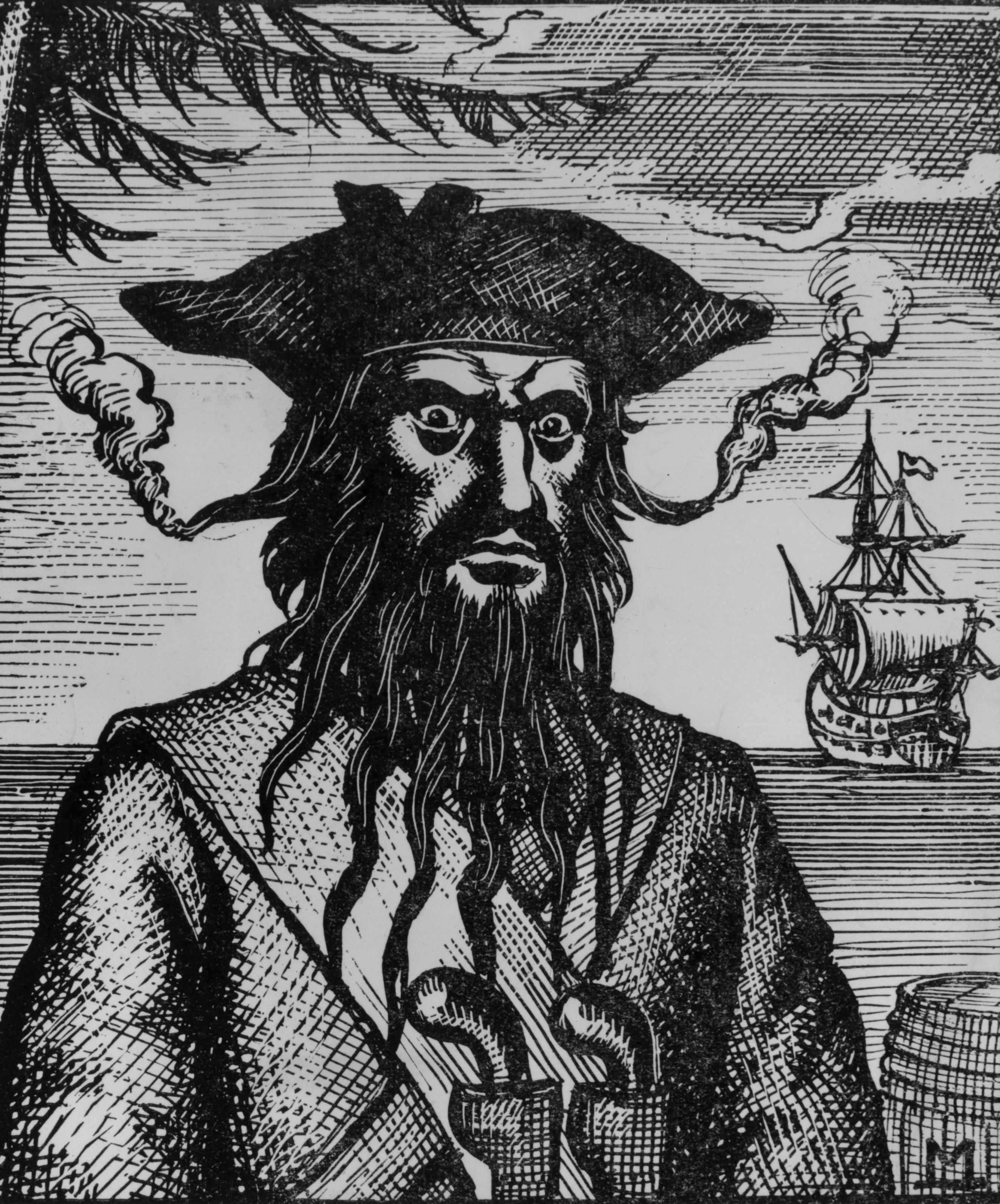

- We might begin with an image similar to this and a similar subsequent slide:

- After students have discussed this opener, perhaps in small groups, they will move on to reading and analyzing two sources:

- Bernal Diaz: The True History of the Account of New Spain (Excerpt)

- http://chnm.gmu.edu/worldhistorysources/sources/conquestofnewspain.html

- While reading this source – or some shortened excerpt – students should be actively highlighting details and commentary. This can be done in a group setting or as a homework assignment. After reading this, they will answer the following questions:

- What were the main details of the Aztecs recorded by Bernal Díaz?

- Why do you think he chose to emphasize these things?

- Who do you think he was writing for? Do you believe he meant for someone else to read this account?

- Relación de Michoacán – Franciscan friar Jerónimo de Alcalá

- http://mansioniturbe.blogspot.com/2011/08/la-relacion-de-michoacan-or-chronicle.html

- While reading this article, students should be actively highlighting details and commentary. This can be done in a group setting or as a homework assignment. After reading this, they will answer the following questions:

- Who is thought to have written the Relación de Michoacán? Compared to the previous source, how is it important that a friar (priest) wrote it instead of a soldier?

- There is a short excerpt from the larger work in the article. Although the book is far too long to read, you can assume that the rest is similar, with an emphasis on the details of history. How is this different from the account of Bernal Diaz?

- How might the author’s intention signal a difference in the perceived importance of the Purepecha culture and people?

- After reading both sources, we will end the lesson with a group project. Students will break into groups of 3-4. In these groups, they will create a graphic representation of the two sources and how they fit into the context of the conquest and colonialism. They should answer the following questions:

- How did the context of the conquest influence different people to write and record different things? The students should give specific examples for each source.

- What are some possible motivations from each historical actor – the friar and the soldier? How are they both similar and different?

- Finally, students should add in a summary that addresses the Essential Question and ties it into specifics of the given examples.

- Bernal Diaz: The True History of the Account of New Spain (Excerpt)

Conclusion:

Although students may come to a variety of conclusions, here is one particularly relevant example. Because the Purépecha were less developed in terms of material culture, the main emphasis of the Spanish conquest on their lands was slave labor in their lucrative mines. There were caches of treasure hidden away for the Cazonci’s son. These were found and looted in due course. However, they did not have the cultural factors of the Aztecs. They did not have the cultural factors that affirmed the Conquistador’s fantasies about the new world. Therefore, there was less of an emphasis recording the culture of Purépecha and more on exploiting their natural resources.

Reflection:

I have a personal connection to this project. An undergraduate professor for whom I was completing an internship was heavily involved in researching the Purépecha. When she passed away from cancer, I was unable to complete the project, for which I had done a lot of research and preparation. That is why I chose to focus on these two cultures. Even so, this is a format that might work for a variety of colonial situations. I would strongly suggest that you bastardize this plan for whatever time period and cultural context you are teaching. The question itself is also applicable to a wider variety of lesson formats.