A lesson in corroboration for 8th grade students

by Christy Thomas

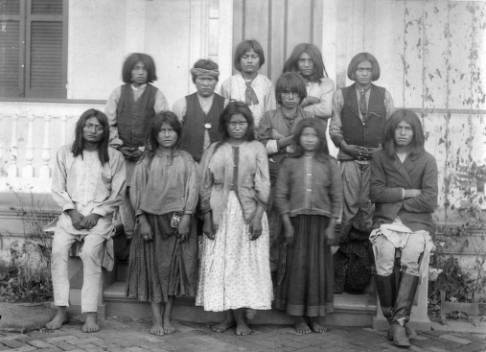

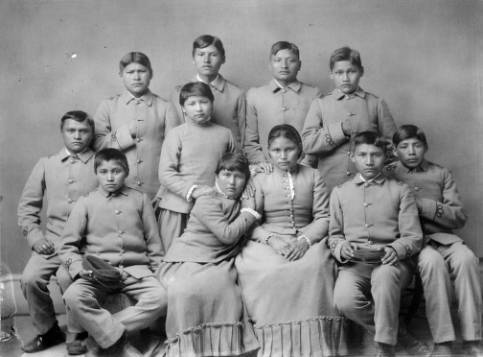

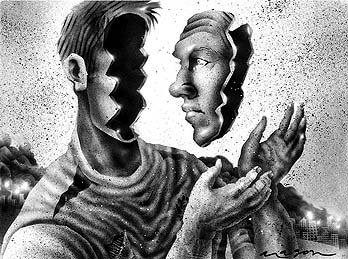

In this lesson, students compare two John Choate photographs from 1886, Chiricahua Apaches as they arrive at Carlisle from Fort Marion, Florida & Chiricahua Apaches four months after arriving at Carlisle. Using the quotations from Sitting Bull and Henry Ward Beecher, students are asked to examine two contrasting pieces of information to learn how Native Americans and the Euro-Americans disagreed on assimilation through education.

“If the Great Spirit had desired me to be a white man he would have made me so in the first place. He put in your heart certain wishes and plans; in my heart he put other and different desires. Each man is good in the sight of the Great Spirit. It is not necessary, that eagles should be crows.”

–Sitting Bull (Teton Sioux)

“The common schools are the stomachs of the country in which all people that come to us are assimilated within a generation. When a lion eats an ox, the lion does not become an ox but the ox becomes a lion.”

–Henry Ward Beecher

Background Information: From the 1879 to 1918, the Carlisle School trained Native American children in academics and trade skills. The school operated on a deserted military base in Central Pennsylvania.

Question 1: As you compare the children in these photographs, what are some of the major changes that took place?

Question 2: Do you believe Sitting Bull and Henry Ward Beecher felt similarly about assimilation? What factors would have caused Sitting Bull and Henry Ward Beecher to view assimilation differently? How do the two messages differ?

Creating a mini-lesson based on historical thinking skills was a great exercise in thinking outside the box. I found it challenging to adjust my thinking from simple recall to more analytical questions. In this lesson, I hope to step outside of a lecture mode and let students take ownership of their learning process. I see emphasizing historical thinking skills as a great way to help students connect the past to the present lives.

I enjoyed working with my classmates to fine tune the mini-lessons. It was nice to work together to improve our final products and discuss the best way to engage students.

Sources:

Images from the Library of Congress Primary Source sets: http://1.usa.gov/1msgsaM

Quotations taken from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School history: http://bit.ly/1msheVi