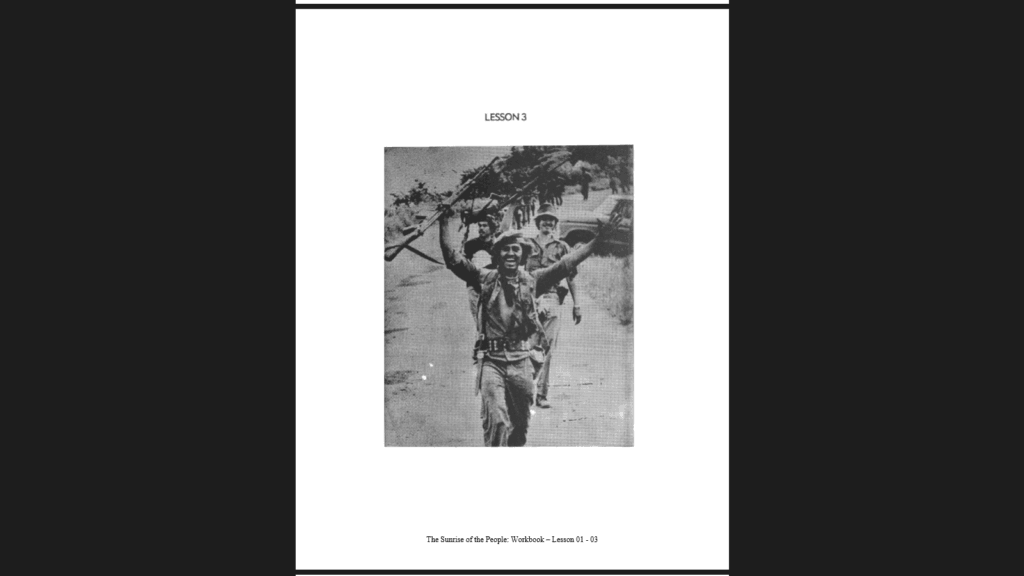

Lesson 3 from El Amancer Del Pueblo (Sunrise of the People), the standard issue Literacy Workbook, with lesson’s generative theme at top.

When I began designing my chapter for our shared iBook, I considered only a handful of ideas before settling on the Nicaraguan Literacy Crusade. Having spent the better part of the last year researching the campaign, becoming intensively familiar with the historiography of the topic, and looking for sources, I had constructed an excellent library of documents and evidence to draw from. The iBook design process offered an opportunity to showcase some of these findings, and choosing such a familiar topic meant that much of the grunt work had already been done. I could focus, almost entirely, on selecting my absolute favorite documents and creating an educational experience built from those sources.

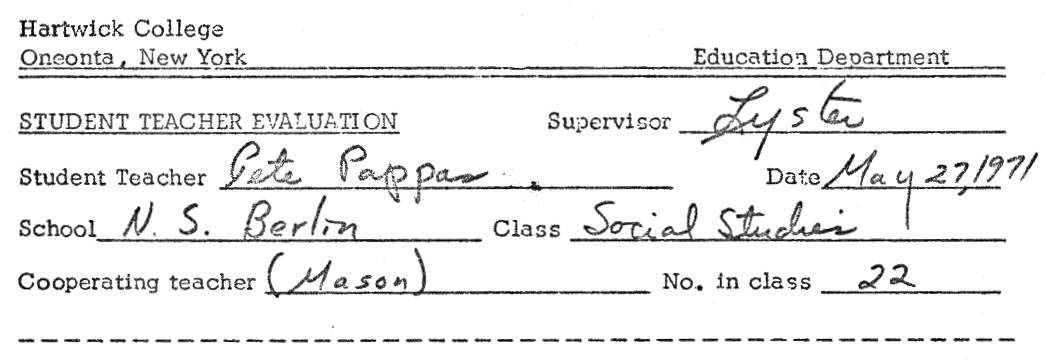

Working within the iBook design process offered another opportunity, however. For months, I have played the role of historian, looking into this topic to discover new understandings, and form new conclusions. The nature of the Document Based Lesson format, which puts students into much of the same role, meant that with some careful planning, I could provide a lesson that would mirror my own experience, and offer students a chance at a history project more closely aligned with how academic historians operate. I sequenced documents in a way that mirrored, in general execution if not in exact similarity, my own research process, and my own journey of discovery. In my lesson, students examine some of the same secondary sources I did to gather context, come to understand the historical event through the same quotes and excerpts I used, and are given a chance to carefully examine the same primary materials I did, with a different but no less meaningful focus.

Image accompanying the generative theme in Lesson 3 from the El Amancer Del Pueblo (Sunrise of the People) Workbook.

One of the aspects of the Nicaraguan Literacy Crusade that drew me to the topic when selecting it for a Thesis, and again when beginning this project, was it’s relevance to both myself and to a degree, all students. The Nicaraguan Literacy Crusade is a story of how a nation came together — albeit in sometimes controversial ways — to better their society. It is a story of relying on the youth to make this vision happen. As an educator, a historical event centered around teaching and instruction naturally appeal to me. But I hope that for students, the emphasis on education can bring some relevance as well. Students spend the lion’s share of their day at school, immersed in an educational system they’ve known in some form almost as far back as they can remember. School is a fixture in student’s lives, and a fixed one at that — a system that changes slowly, is defined by the past, and presents one narrative of what education is and what it should look like. Creating a lesson about a project where middle- and high-school aged students not only played a vital role in a national endeavor, but also served as teachers themselves, opens up an opportunity for students to step outside this system and reflect on the differences between different ways we educate. Perhaps, in the process, they can begin to think critically about their own education, and the structures that facilitate that education.

Designing a book like this could be challenging at times, from a mundane technical standpoint, but that challenge never seemed so big as to obstruct the overall goal. iBooks Author proved to be intuitive enough, for me at least, to make the real difficulty of this assignment the challenge of sequencing interesting content and providing meaningful questions to accompany that content. Finishing the chapter was extremely rewarding, both due to the sharp professional look of the book, and the satisfaction of being able to incorporate an event I find fascinating into a new and fresh format. This was a fresh look on a topic I have spent much time looking at already, and the new perspective was valuable and refreshing. Knowing that I already had most of the documents I needed due to prior research additionally reinforced to me the value of the skills I have acquired to find sources in the future, for future, similar projects as this.

Republica De Nicaragua. Cruzada Nacional De Alfabetizacion. Ministerio De Educacion. El Amancer Del Pueblo. Republica De Nicaragua, 1980.