I admit to being guilty of dominating classroom discussion as a rookie social studies teacher. “Class, what were three results of the War of 1812? … Anyone? … Anyone??”

After years of facing this type of discussion, students learn that their comments are of provisional value until “approved” by the teacher. Over time, students stop listening to each other and only focus on what the teacher says or validates – “will that be up on a test?” When students are put in small group discussion, they rapidly get off subject. With no teacher to validate their comments, they naturally gravitate to other subjects where peer comments are valued – “what are you doing this weekend?”

Today’s class will explore strategies and resources for taking the teacher out of the role of information gatekeeper and encouraging productive student-centered dialogue.

Students were directed to explore the discussion techniques I have assembled on our edMethod’s Toolkit: Student-Centered Prompts And to follow links to Teachers Toolkit | OETC PLN Strategies They were prepared to either demonstrate a discussion they liked or talk about their experience leading discussion in the placements.

Additionally we will explore the Structured Academic Controversy (SAC) model. Not all issues can be easily debated as pro / con positions. SAC provides students with a framework for addressing complex issues in a productive manner that builds their skills in reading, analyzing, listening, and discussion. It shifts the goal from “winning” the argument to active listening to opposing viewpoints and distilling areas of agreement. If time permits we will try an example “Was Abraham Lincoln a racist?”

Students might enjoy my series “Great Debates in American History”

Assignment: Write a blog post as a reflection on the challenges and opportunities of organizing productive classroom discussions.

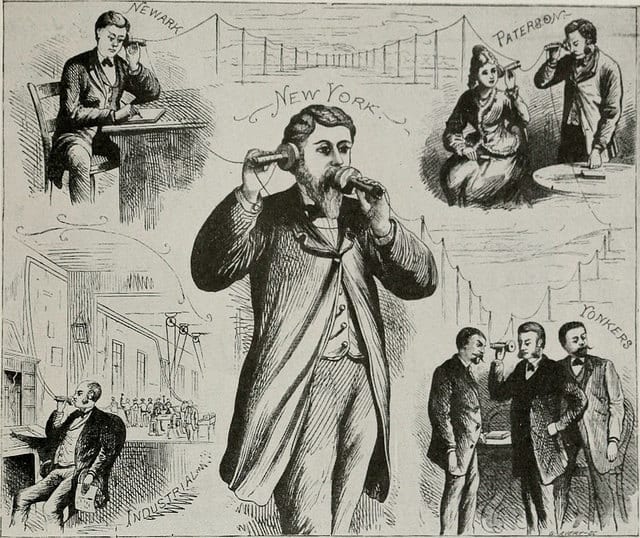

Image credit: From the Scientific American (1887) and reprinted in “Bell Telephone Magazine” (1922) Internet Archive Book Image

Descriptive text states: Our large engraving . . . affords an excellent idea of how the instrument is used… . The figure marked New York may be con-sidered as a public speaker delivering a lecture to be heard in the towns mentioned. He talks into one telephone while he holds another to his ear, in order, for example, to hear the applause, etc., of his auditory; or he may be maintaining a discussion or debate, and he then hears his adversary’s replies or interruptions. Now,at Newark there is simply a reporter,who takes down the speech phonographically; the words pass on through that telephone and reach Paterson.