The class I am student teaching in just finished a unit on the Colonial period in America. We are now beginning a unit on the American Revolution, so I thought the topic for my Document Based Question, or DBQ, assignment should be the American Revolution. Using this topic will give me ideas and help me plan future lessons for my class. The essential question I want my students to answer in the DBQ is: Did the American Colonists have legitimate motivations for initiating war and separating from Britain? There are countless documents available for this topic and question, so it is important for me to pick documents that students will be able to interpret questions, such as: What does it say? How does it say it? And what’s it mean to me? I want the students to use evidence to support their answers to the questions pertaining to each document and form an argument based on what they have learned and think. I will use documents such as letters, speeches, governmental records, and pictures so students have a variety of documents from different sources. While I develop my DBQ, I have to make sure I put the students in the role of the historians.

Example Document:

Association of Members of the Late House of Burgesses, 27 May 1774

We his Majesty’s most dutiful and loyal subjects, the late representatives of the good people of this country, having been deprived by the sudden interposition of the executive part of this government from giving our countrymen the advice we wished to convey to them in a legislative capacity, find ourselves under the hard necessity of adopting this, the only method we have left, of pointing out to our countrymen such measures as in our opinion are best fitted to secure our dearest rights and liberty from destruction, by the heavy hand of power now lifted against North America: With much grief we find that our dutiful applications to Great Britain for security of our just, antient, and constitutional rights, have been not only disregarded, but that a determined system is formed and pressed for reducing the inhabitants of British America to slavery, by subjecting them to the payment of taxes, imposed without the consent of the people or their representatives; and that in pursuit of this system, we find an act of the British parliament, lately passed, for stopping the harbour and commerce of the town of Boston, in our sister colony of Massachusetts Bay, until the people there submit to the payment of such unconstitutional taxes, and which act most violently and arbitrarily deprives them of their property, in wharfs erected by private persons, at their own great and proper expence, which act is, in our opinion, a most dangerous attempt to destroy the constitutional liberty and rights of all North America. It is further our opinion, that as TEA, on its importation into America, is charged with a duty, imposed by parliament for the purpose of raising a revenue, without the consent of the people, it ought not to be used by any person who wishes well to the constitutional rights and liberty of British America. And whereas the India company have ungenerously attempted the ruin of America, by sending many ships loaded with tea into the colonies, thereby intending to fix a precedent in favour of arbitrary taxation, we deem it highly proper and do accordingly recommend it strongly to our countrymen, not to purchase or use any kind of East India commodity whatsoever, except saltpetre and spices, until the grievances of America are redressed. We are further clearly of opinion, that an attack, made on one of our sister colonies, to compel submission to arbitrary taxes, is an attack made on all British America, and threatens ruin to the rights of all, unless the united wisdom of the whole be applied. And for this purpose it is recommended to the committee of correspondence, that they communicate, with their several corresponding committees, on the expediency of appointing deputies from the several colonies of British America, to meet in general congress, at such place annually as shall be thought most convenient; there to deliberate on those general measures which the united interests of America may from time to time require.

A tender regard for the interest of our fellow subjects, the merchants, and manufacturers of Great Britain, prevents us from going further at this time; most earnestly hoping, that the unconstitutional principle of taxing the colonies without their consent will not be persisted in, thereby to compel us against our will, to avoid all commercial intercourse with Britain. Wishing them and our people free and happy, we are their affectionate friends, the late representatives of Virginia.

The 27th day of May, 1774.

Signed by 89 members of the Late House of Burgesses.

Example Document Questions:

- What does this document say about the colonists?

- Is there a tone within the writing of the document?

- What actions of the British upset these people?

- What did these colonists recommend be done?

- How did these Virginia colonists feel about what was happening in Massachusetts?

- What does this document mean to the future of the Colonies and British relationship?

Reflection:

The process we have used to peer review my ideas have been really helpful. I received great feedback from the “speed dating” of our ideas activity, which helped me further develop my DBQ. The challenges I have faced are coming up with quality questions for each document that will connect back into my essential question. From this process, I am learning to always make sure the student is the historian in the classroom and to make sure I am asking higher level thinking questions for my students. This assignment builds upon the work we did on historical thinking earlier in the semester because I constantly refer to the SHEG website and historical thinking chart. I have to make sure the students are involved in historical thinking skills such as sourcing, contextualization, corroboration, and close reading.

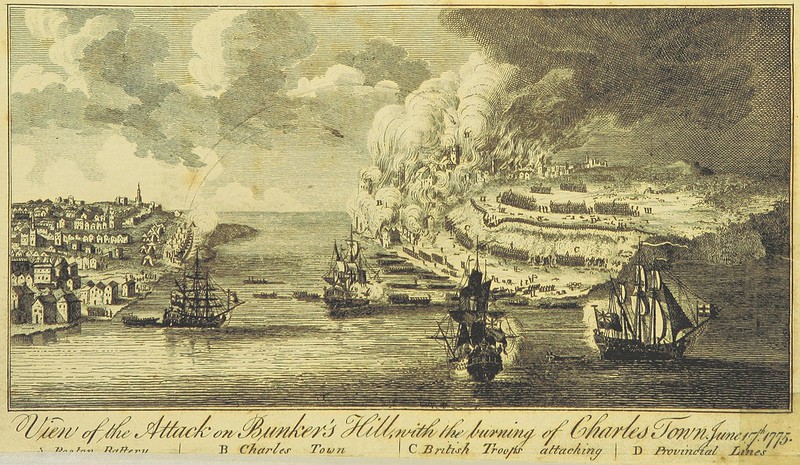

Image credit:

Image taken from page 6 of ‘The American War; a poem in six books, etc. [By G. Cockings.]’ 1781

The British Library 003734518