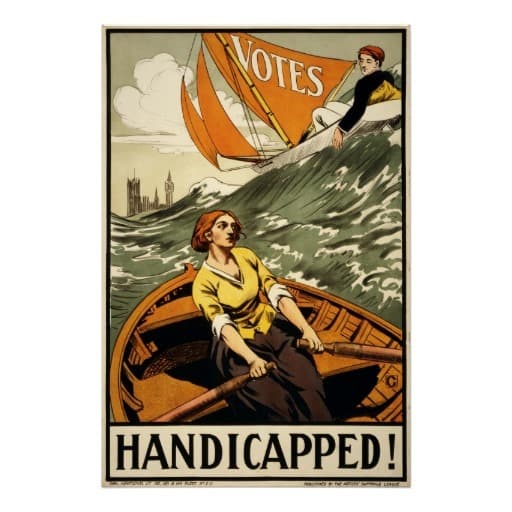

When we first started working on this DBQ we knew that we wanted to educate students on how to best analyze propaganda, understanding what each piece is trying to say, being able to discover how each piece goes about conveying its message, and what historical events are transpiring to bring about such pieces of work. At the beginning of this DBQ lesson there was talk of only showing pro-women’s suffrage propaganda, but we discovered that if the students had only positive propaganda to view, then the lesson loses some of its strength. As a result we had to make a slight change my overall lesson. Instead of using only pro-suffrage pieces, we would also use anti-suffrage pieces and the students would compare, contrast, and analyze these pieces as a whole as well instead of independently.

When we first started working on this DBQ we knew that we wanted to educate students on how to best analyze propaganda, understanding what each piece is trying to say, being able to discover how each piece goes about conveying its message, and what historical events are transpiring to bring about such pieces of work. At the beginning of this DBQ lesson there was talk of only showing pro-women’s suffrage propaganda, but we discovered that if the students had only positive propaganda to view, then the lesson loses some of its strength. As a result we had to make a slight change my overall lesson. Instead of using only pro-suffrage pieces, we would also use anti-suffrage pieces and the students would compare, contrast, and analyze these pieces as a whole as well instead of independently.

I personally believe that the final project achieved all of my learning goals. My partner had a large amount of excellent material that we used and as a result we were able to created a DBQ that pushes students to both compare and contrast multiple pictures, as well as analyze individual pictures at a deep level.

The biggest lesson that I learned while working on this DBQ is that you have to be careful with what photographic material you use. Pictures are one of the most important parts of a DBQ and if the DBQ has poorly chosen pictures than the overall quality of it will suffer greatly. I also learned that you need to be careful when choosing a topic. While something such as the women’s suffrage movement is well documented through images and propaganda, there are other events that are either lacking sufficient pictures or lack any diversity in their imagery.

This DBQ is part of our class-produced, multi-touch iBook. Available free at iTunes

You can find our DBQ at Learnist

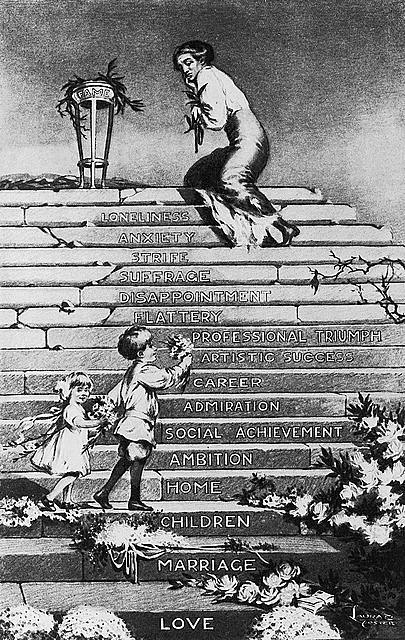

Image credit: Library of Congress: LC-DIG-ppmsca-02940

Title: Looking backward / Laura E. Foster.

Creator(s): Foster, Laura E., artist

Date Created/Published: c1912 August 22.