Historical Context: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study began in Macon County, Alabama in 1932. This was during the Great Depression in the deep south, an area where Black sharecroppers worked tirelessly for low-pay. Jim Crow laws, segregation, and racial prejudice were a huge part of daily life for the poor and often uneducated workers in this area.

At this same time, syphilis was a disease spreading rampantly around the world. This Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) would begin with painful sores and eventually, if left untreated, move on to attack the nervous system, including the brain, nerves, eyes and heart. There was no proven treatment for the disease. Researchers from the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) theorized that the disease affected the nervous system of white people more often, and the cardiovascular system of Black people. There was little evidence for this, however there are many examples throughout history of the same sorts of racial prejudice in the medical field. In order to study this theory further, PHS researchers found a group of men in Macon County to test their hypothesis on.

600 men were selected for this study. 399 were identified to have syphilis and 201 did not test positive for the disease. The purpose of this PHS study was to compare untreated syphilis in the group of 399 against the group of 201 who did not have the disease and study the differences over their lifetimes. The group of the 399 participants were not told they had syphilis, instead being told they had “bad blood” and would receive free treatment through this study. The purpose of the study was never explained to the participants, which is a practice researchers call giving the participants Informed Consent.

In 1942 penicillin was first developed for widespread use. In 1947, the antibiotic was identified as an effective treatment for syphilis. PHS researchers in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study decided at this time not to provide the men in their experiment with penicillin, which would have cured their disease, instead continuing to give them a placebo in place of any real treatment.

In the mid-1960s a PHS disease investigator named Peter Buxton found out about this study. He reported to his superiors that he was concerned with the ethical and moral issues apparent. Supervisors at PHS reviewed the case, but ultimately decided to continue to continue the study. As men identified in the original study were dying, their bodies would be collected and autopsied by PHS, and the findings were determined too important to stop the study.

Peter Buxton continued to feel uneasy about what was happening, and contacted Jean Heller, a reporter for the Associated Press. Jean Heller broke the story in 1972, and amid a massive public outcry, the study was disbanded. To this day it is unknown how many people were affected by this disease which has been treatable since 1947.

Further Information and Context:

- Tuskegee University article “About the USPHS Syphilis Study”

- History.com article “Tuskegee Experiment: The Infamous Syphilis Study”

- Newsy video “The Unknowns about the Tuskegee Syphilis Study

- TedEd video “Ugly History: The U.S. Syphilis Experiment- Susan M. Reverby

Essential Questions:

- When should an individual take a stand against what they believe to be an injustice? What are the most effective ways to do this?

- What are the causes and consequences of prejudice and how does an individual or group’s response to it reveal their morals, ethics, and values?

- How do racial stereotypes influence how we understand the world?

- When is it moral for scientists to study on human subjects, if the findings are “for the greater good?” Who determines what the greater good is?

Assignment: This lesson will utilize the historical thinking skills of sourcing and contextualization. Students will be asked to review images and text which assess their critical thinking skills of how a source provides a perspective on an historical event, how time and place influence a historical document, and how historical documents shape our understanding of history. Students will respond to guiding questions provided for each resource which will ultimately tie back to the larger themes presented in the essential questions.

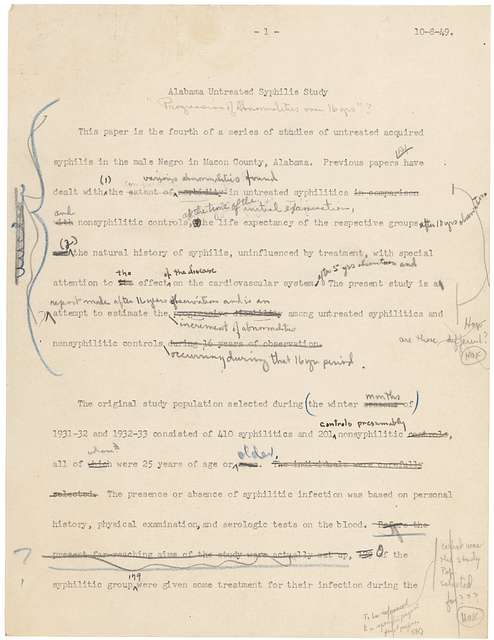

Document One: Experiment Draft Report pages 1 and 2

Examine the pages of this draft report on the study. What is the purpose of the study as stated? What could be reasons for the edits in pencil? What jumps out at you as interesting about the edits? When was this report written and what do we know about the treatment of syphilis by this date?

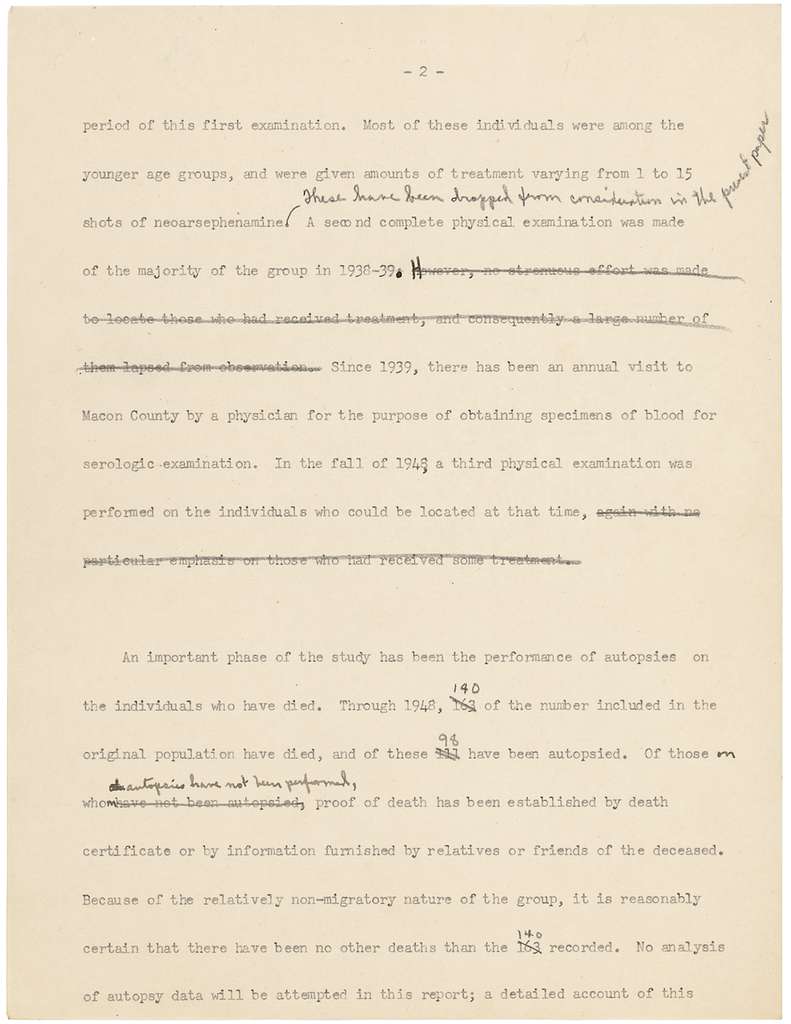

Document Two: Classification Data

This is a classification set of data for the experiment, outlining factors of the men involved in the experiment. When was this data published and what do we know about the treatment of syphilis at this time, and the ethics concerns raised at the PHS by this time? What questions does this document raise about deaths as a result of this study? Since we know syphilis is sexually transmitted, what questions does this document raise about total deaths as a result of this study? Does this document give us any insight into how the researchers viewed the participants of this study?

Document Three: Images of Participants

What do we know about the lives of the men who participated in this study? How might the circumstances of living in the deep South under Jim Crow laws have influenced the ability of these men to advocate for themselves, or even to understand the purpose of the study? In these images the men are seen picking cotton. How can we compare and contrast the system of slavery with the syphilis study in the context of access to and ownership over the bodies of Black people?

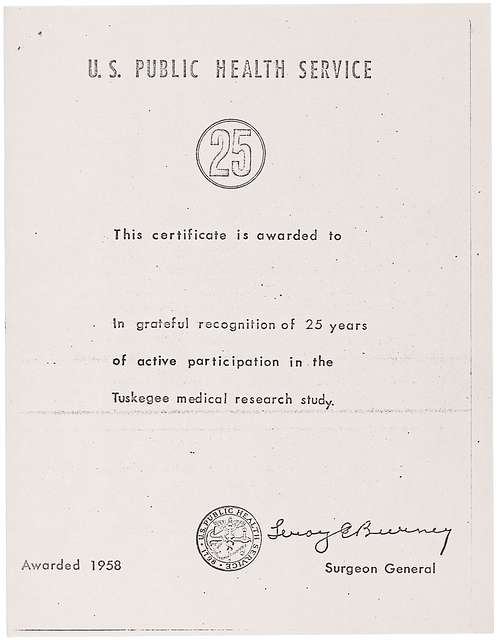

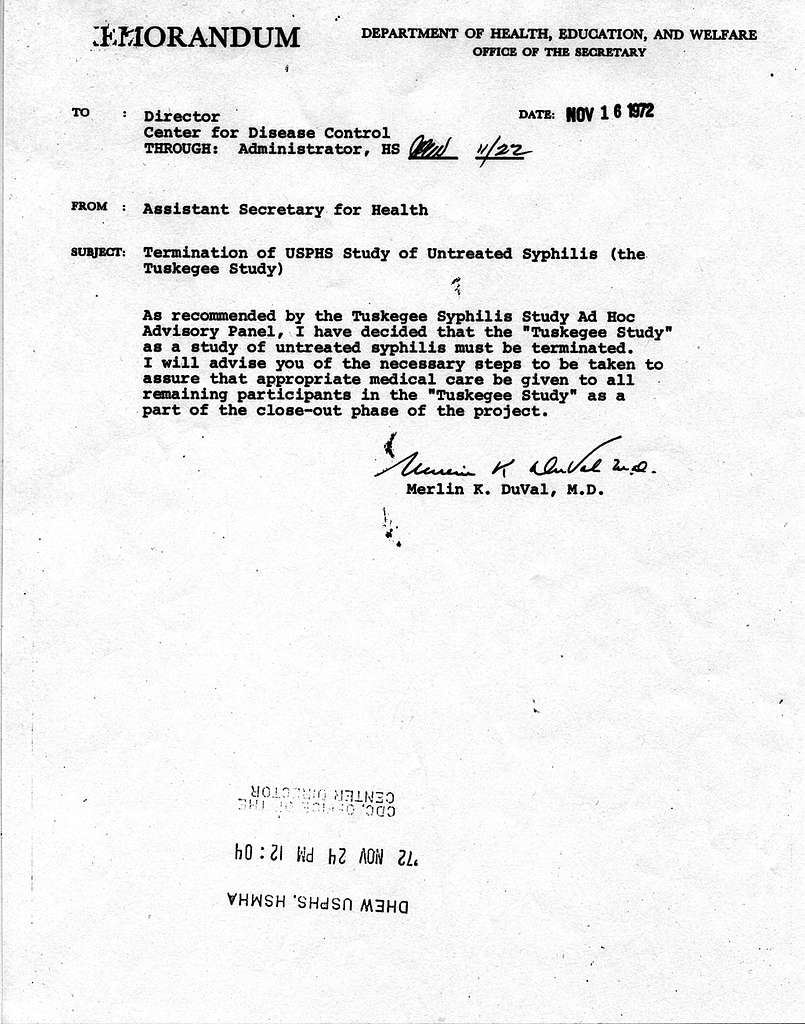

Document Four: Memorandum re Termination of the Study and Thank You to Study Participants

How does (if at all) the Memorandum document address the reasons for the termination of this study? What do we know about the article written by Jean Heller and how this memo is a response to the publishing of that article? How do the memo and thank you certificate compare and contrast based on the date they were published in telling us how the U.S. government felt about this study?

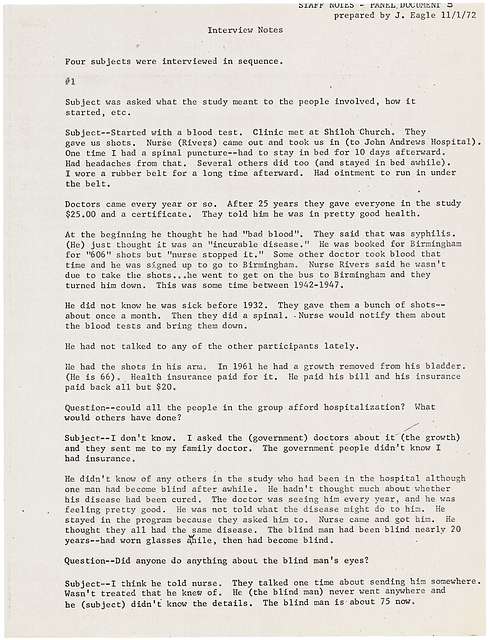

Document Five: Interview Transcript and Images of Participants

How does this interview transcript give us more insight into the way the participants of the study were deceived or mislead about the purpose of the study? What do we know about the shots, spinals, and treatments given to the groups identified to have syphilis? Why are the details about the man who went blind important in the context of the study and of the symptoms of untreated syphilis?

Final Thoughts:

An assignment of this sort may lend itself to shorter writing samples from the leading questions above each image, or possibly a longer essay responding to one of the essential questions. Students would be encouraged to connect this event to others in history and research further on questions which arise for them during the lesson (student questions are always preferable to the ones I come up with!). Students may also want to do some further reading on the participants of this study, and this CBS article from 2017 from the family members of participants may be a good place to start.

Olivia, this is some hard stuff to learn. You made it approachable and still maintain the gravity of the event. The inclusion of the written documents was chilling, but a good way for students to read the very words that started and ended this chapter in history.

Olivia,

This is a top-notch lesson! Everything from your historical context to the sources you chose are of extreme quality! I learned a lot by reading the historical context you provided and then applying this knowledge to the different types of curated sources. I can imagine myself being a high school student and feeling like a real historian by participating in this lesson. Heck, I feel like this is the case even now!

Amazing job!!!

One more thing to note: I learned about the Tuskegee Syphilis Study in high school, but it was a secondary source out of a book… this downplayed the severity of the event. Had I seen these fascinating (yet very disturbing) primary sources, I would have learned SO much more

The lesson opens with a detailed historical context. It’s well written and guides the student to an understanding of the setting at a variety of levels – from the disease, to study, to larger considerations of black life in Jim Crow South. I especially appreciate the links to more detailed background information.

I think the essential questions are especially well-crafted. While they are firmly rooted in the specifics of this case, they draw the student to more timeless and overarching considerations. The framing of the historical thinking skills is especially well-written and should direct students to the essentials of the task.

You’ve done an excellent job of finding and curating some very powerful documents to support the task. They are well introduced and supported with detailed scaffolding questions.

Brava! Overall this is a first rate lesson that embodies the historical thinking skills we worked hard to develop this term. While the topic of the lesson is shocking, it’s an important story that needs to be told. Especially its legacy in the public health trust gap in the black community

Really excellent lesson, Olivia.

I had a base understanding, but I learned so much from this lesson. I cannot believe it went on as long as it did.

Disturbing and shameful, but, like Bruce said, you approached it with grace- illuminating histories shadows.

Loved (but hated) reading this.

Thank you!