Mini-Lesson Created by: Alekzandr Wray

Target Students: 10th Grade

SHEG Skills: Close Reading, Sourcing, Contextualizing

Learning Topic: Runaway Slaves

Essential Question: What were the narratives being told about/by enslaved runaways during the 1850s?

Description: Students will discuss three documents which illustrate the perspectives of historic stakeholders in the issue of enslaved runaways. The first document, an excerpt from Frederick Douglass’ “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave”, recounts his experience at the slave breakers’, Mr. Covey, property. The second document is about Drapetomania, a mental illness attributed to enslaved runaways by Samuel A. Cartwright. Finally, the third document is a reward poster published in Washington, D.C. by a local enslaver. Each document plays off of each other to paint different perspectives on the issue. Students will be asked to work in partners or in small groups to discuss scaffolding questions after each segment to further understanding.

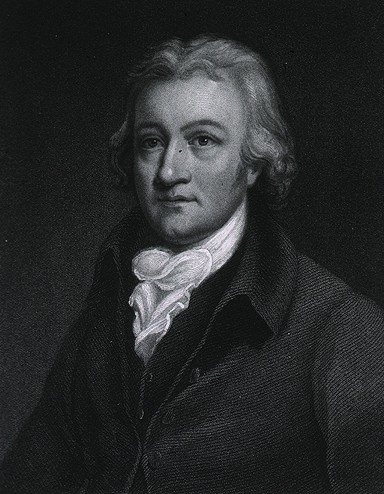

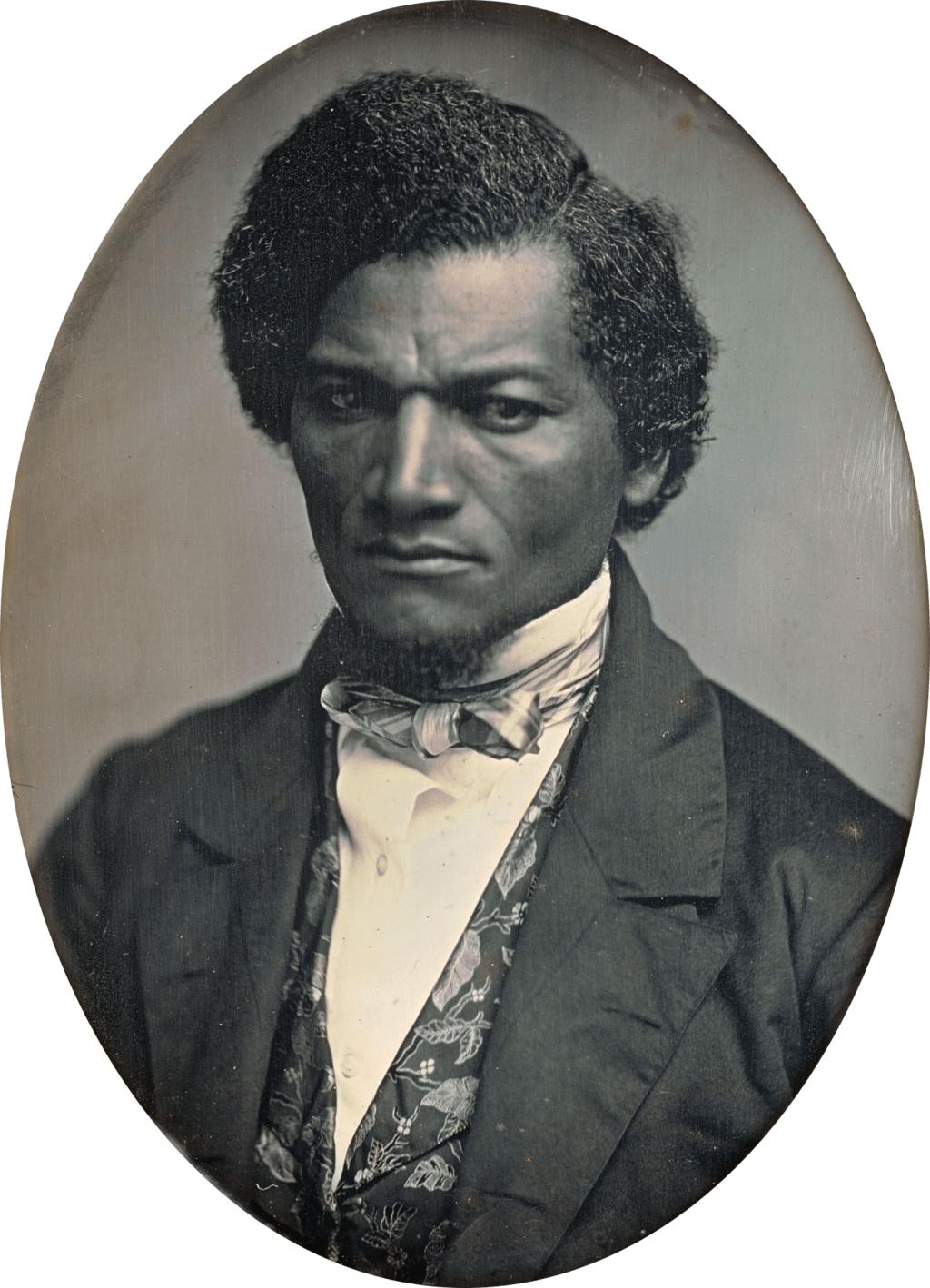

Part I: Frederick Douglass & Mr. Covey

Students work in pairs to read the article, discuss it, respond to the prompts and take notes on their conversation.

Fredrick Douglass recalls being sent to Mr. Covey, a slave breaker (1833, Maryland)

“Master Thomas at length said he would stand it no longer. I had lived with him nine months, during which time he had given me a number of severe whippings, all to no good purpose. He resolved to put me out, as he said, to be broken; and, for this purpose, he let me for one year to a man named Edward Covey. Mr. Covey was a poor man, a farm-renter. He rented the place upon which he lived, as also the hands with which he tilled it. Mr. Covey had acquired a very high reputation for breaking young slaves, and this reputation was of immense value to him. It enabled him to get his farm tilled, with much less expense to himself than he could have had it done without such a reputation. Some slaveholders thought it not much loss to allow Mr. Covey to have their slaves one year, for the sake of the training to which they were subjected, without any other compensation. …

If at any one time of my life more than another, I was made to drink the bitterest dregs of slavery, that time was during the first six months of my stay with Mr. Covey. We were worked in all weathers. It was never too hot or too cold; it could never rain, blow, hail, or snow, too hard for us to work in the field. Work, work, work, was scarcely more the order of the day than of the night. The longest days were too short for him, and the shortest nights too long for him. I was somewhat unmanageable when I first went there, but a few months of this discipline tamed me. Mr. Covey succeeded in breaking me. I was broken in body, soul, and spirit. My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished, the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me; and behold a man transformed into a brute!”

Scaffolding Questions:

- Who was Frederick Douglass and from what perspective was he writing?

- What was Douglass’ experience like with the slave breaker?

- Who do you think was Douglass’ intended audience when reflecting on his experience?

- Why did experiences like Douglass’ lead many slaves to runaway? Why did they cause many to stay?

- What parts of the passage stand out the most to you and why?

- How does the concept of “breaking” a slave land for you? What do you think that means?

- Can we trust him as a source for how slavery was? Why?

Part II: Drapetomania & Samuel A. Cartwright

Part II: Drapetomania & Samuel A. Cartwright

Students will each have a copy of Cartwright’s description of Drapetomania and will work in a group to discuss the article, while a scribe takes notes, and review the scaffolding questions.

Scaffolding Questions:

- Who was the author of the article, what did he do and what role did he serve?

- What was he writing about? What was his perspective? Who was his audience? What/who could he have been influenced by?

- Where in the United States was this article written and when?

- Why was “science” used to connect enslaved runaways to a mental “malady”? What purpose did it serve?

- What two types of treatment by enslavers did Cartwright claim were the chief primary causes of drapetomania?

- Is Cartwright a reliable source to consider when discussing enslaved runaways?

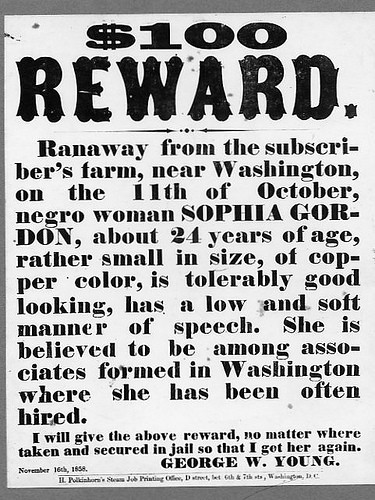

Part III: $100 Reward, “… so that I get her again.”

Part III: $100 Reward, “… so that I get her again.”

Again, students will work in a small group to analyze the document, start a conversation using the scaffolding questions, and take notes to turn in.

- Who wrote this poster?

- Who are the beneficiaries of this poster? Who loses?

- What is the article’s purpose?

- Where and when was it written?

- How much is $100 in 1858 worth in today’s money?

- What gave enslavers the right to offer rewards for the capture/return of a human being?

- Why were posters like this common during this era?

- Does this poster give a reliable description of Sophia? Why? If not, what are the costs of its unreliability?

- What were some of the impacts of posters like this?

- Have you seen posters like this today? If so, where and who/what was the poster about?

Reflection: I believe what I put together is more of a series of mini-lessons that all connect rather than one mini-lesson that stands by itself: I’d likely have to dedicate a few class periods to teach this activity in order to do it justice. In the future, I’ll likely add an additional section to the presentation that covers the abolitionist viewpoint on the issue and then ask students questions that delve into corroboration territory; doing so would allow students the opportunity to tie each of the different sources together in order to create a larger view of the issue.

An aspect of the mini-lessons that I appreciate is that, at each step of the process, students are allowed to utilize community to further their own understanding and because each group will have a scribe to take notes on their conversation, the teacher can gain some really revealing information into her/his students’ thought process when they’re not being hovered over. That information can help determine where the large group conversation should lead and could be useful in deciding what future activities, if any, need to be planned for this topic.

Sources:

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass:

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (Boston: Anti-Slavery Office, 1845).

Reprinted in Eyewitness to America, David Colbert (Pantheon Books, NY) 1997 p 143-146

To follow up on our discussion of the language of slave era … I heard Laurie Halse Anderson speak on Saturday and she preferred the term “self-liberating” to “runaway” slave.

I thought the scaffolding questions were very focused and as you point out in your reflection; this is something that could certainly be many smaller lessons. Good job