In most educational settings, history is often taught in a stale, immovable way. This was my experience until my junior and senior years of high school, when I was lucky enough to have several teachers who valued making history feel tangible and valuable to the lives of students. The main way my teachers created this feeling was by viewing the same historical event through multiple lenses.

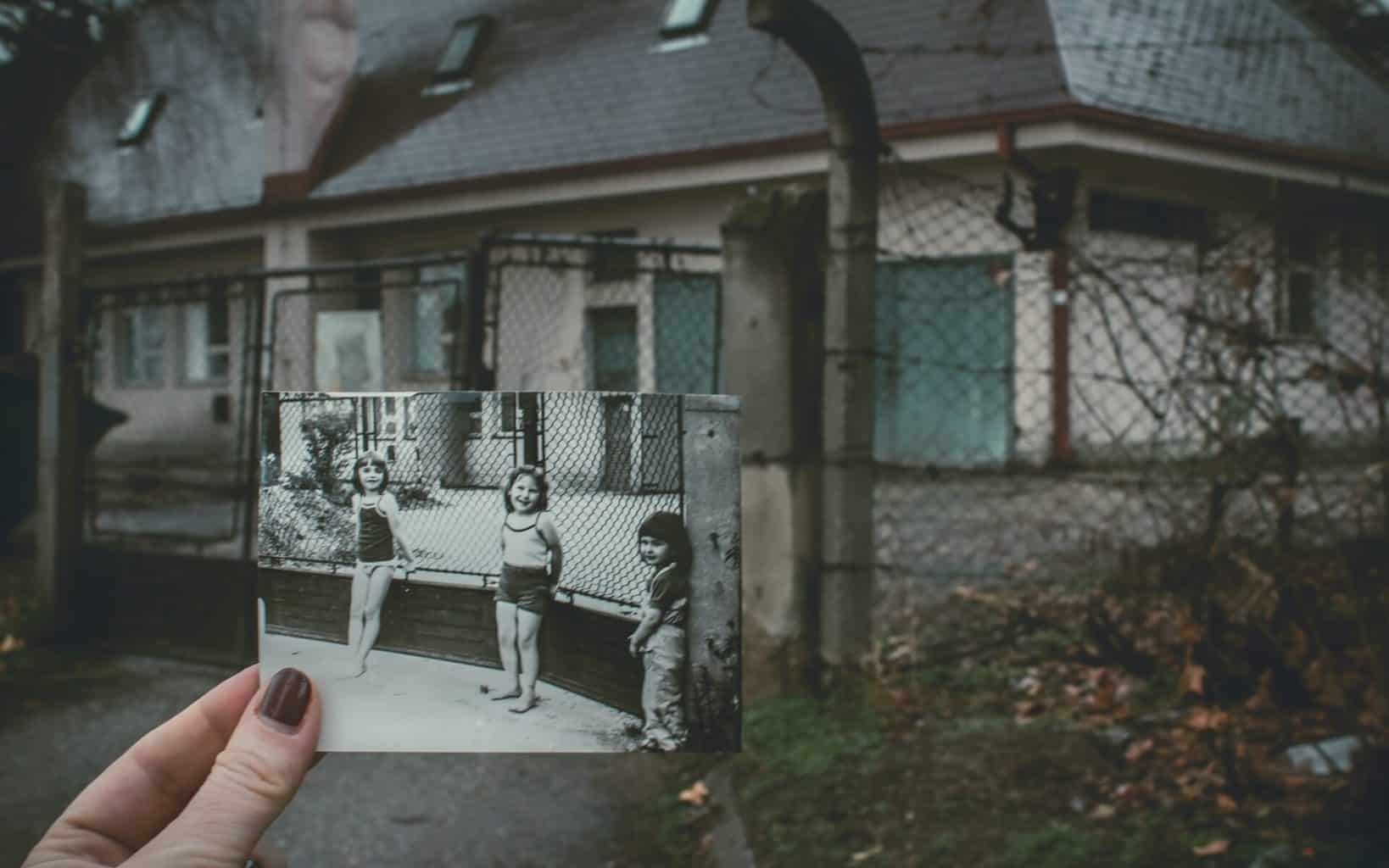

Prior to this point in my education, I had been taught that there was one true story of history, the only story. In my junior year History of the Americas class, my world was opened up to the truth and validity of multiple points of view for the same subject. This was introduced by analyzing the same historical events, such as Columbus’ conquest, banana republics, the Mexican-American War, etc. from perspectives of multiple sides. We analyzed first- and second-person accounts, historical texts and timelines, and even incorporated examination of magical realism literature to strive to reach a fuller picture of how history can mold the experiences of many different people in varying ways. History did not feel dry or perfunctory, but instead took on so much emotion and connectedness.

My teachers never discouraged us from sharing our own perspectives as well, allowing us to partake in history and therefore making it more important to our own lives. This was particularly important during the subjects of the 9/11 attacks and the Arab-Israeli conflict. We would often have discussions before a unit, where we would discuss what we knew about a subject, maybe with an introductory overview taking place first to help aid the discussion. This also allowed my teachers some form of assessment in order to scaffold knowledge into the class based on what was already known about the subjects. Discussion or debate often led to a lot of emotion over the topics, and I appreciate that my teachers never shied away from facilitating difficult conversations.

For me, what was most impactful from those classes were the reviews at the end, which were often written assessments of what we had learned, what affected us the most, and what questions we still had. From seeing many perspectives on a historical event, it made me feel the validity of my own point of view and those of my peers, knowing that history did not exist in some untouchable place in the world. The amount of freedom we were afforded really bolstered our autonomy in terms of Self-Determination Theory, and made us value ourselves and our place in history.

Featured image by Shelagh Murphy on Unsplash