Beginning in Class 4, we began a study of historical thinking skills based on the work of Sam Wineburg and the Stanford History Education Group (SHEG). We focussed on three key skills – Sourcing, Contextualizing and Corroborating. Students were assigned the task of designing their own historic thinking skills lesson based on that model and collecting them in a shared Google presentation. We took time in Class 5 to do some peer evaluation of the work. As a final assignment, students were asked to reflect on the process and use their lesson as the basis for a blog post. See them all here.

The Only Thing We Have to Fear is Not Being Able to Correctly Identify These Speeches (and Fear Itself)

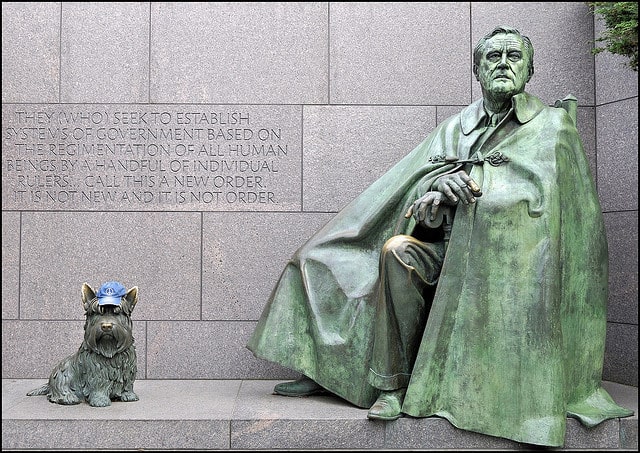

Photo Credit: Tony Fischer

Target: 8th or 11th grade (caliber of questions can be tailored based upon grade)

Historic Skills: Contextualization

For Students: The following two excerpts are both from inaugural speeches given by FDR. Based upon what you know about the time during which FDR served as president, respond to the following prompts:

- Which speech do you think came first? Why?

- Out of the four inaugural addresses that FDR gave, which do you think these two are? Explain your rationale.

- What common themes do you see in these speeches?

For Teachers: Students should have enough knowledge about FDR’s presidency that they will be able to identify what issues he was addressing in each speech, and be able to put them into context. They will be able to pick up on the fact that he was far more verbose in the first speech given than the second, indicating that this was his first, or at least an earlier speech. By the time he gave the second, he was used to doing this, and the people were used to hearing from him, thus he felt less of a need to be so wordy. They will also notice the repeated calls to be courageous during this time.

Note: The dates attached to the speeches would not be provided, but are included for the reader’s knowledge.

Speech #1

“I am certain that my fellow Americans expect that on my induction into the Presidency I will address them with a candor and a decision which the present situation of our Nation impels. This is preeminently the time to speak the truth, the whole truth, frankly and boldly. Nor need we shrink from honestly facing conditions in our country today. This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance. In every dark hour of our national life a leadership of frankness and vigor has met with that understanding and support of the people themselves which is essential to victory. I am convinced that you will again give that support to leadership in these critical days.”

–FDR’s First Inaugural Address. March 4, 1933

Speech #2

“Mr. Chief Justice, Mr. Vice President, my friends, you will understand and, I believe, agree with my wish that the form of this inauguration be simple and its words brief.

We Americans of today, together with our allies, are passing through a period of supreme test. It is a test of our courage—of our resolve—of our wisdom—our essential democracy.

If we meet that test—successfully and honorably—we shall perform a service of historic importance which men and women and children will honor throughout all time.

As I stand here today, having taken the solemn oath of office in the presence of my fellow countrymen—in the presence of our God—I know that it is America’s purpose that we shall not fail.”

–FDR’s Fourth Inaugural Address. January 20, 1945.

Reflection: As usual, I felt that the class review process went smoothly. I have used Google Docs to work on projects with people before, so I was already fairly comfortable using the comments option. It was a fun experience being able to incorporate that into a class. While working on these lessons was fun, I still strongly believe that these SHEG inspired activities are still best suited for being used as a warm-up, or part of a review session. An entire lesson could not be taught on this. Perhaps by combining a few slightly different formats of this activity, you could teach an entire lesson on thinking like a historian and examining documents. Beyond that though, this is just a quick exercise.

Dr. Seuss on Domestic Security

A mini-lesson on WWII cartoons by

Kristi Anne McKenzie

Historical Content: World War II (home front)

Historical Skills: Contextualization, sourcing

Intended Grades: 9-12

Directions:

Use the source information, your knowledge of history, and the video and political cartoons to answer the questions below.

Sources:

Document A is an animated short film written by Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss) and P.D. Eastman and produced by Warner Bros. for the War Department as part of the U.S. Army Air Force First Motion Picture Unit. Documents B, C and D are political cartoons created by Dr. Seuss for PM, a New York City daily newspaper.

Document A: Private SNAFU in Rumors

Question 1: When was the film produced?

Question 2: Which two of the facts below might help explain why the author wrote this screenplay?

- After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Dr. Seuss, like many Americans, developed a concern for national security and a fear of foreign enemies.

- Private SNAFU cartoons were only shown on military bases; they were not allowed to be shown to the general public. As they were a product for the use of the War Department, the films did not have to comply with standard censorship regulations in regards to decency or colorful language.

- In order to keep the animation studios open during the war, companies like Warner Bros. had to produce military training films.

- The goal of the Private SNAFU films was to teach lessons on secrecy, military protocols, and disease prevention to soldiers with poor reading skills.

Question 3. Now compare the film “Rumors” with the three political cartoons. How is the intended audience similar and different? How is the intended message similar and different?

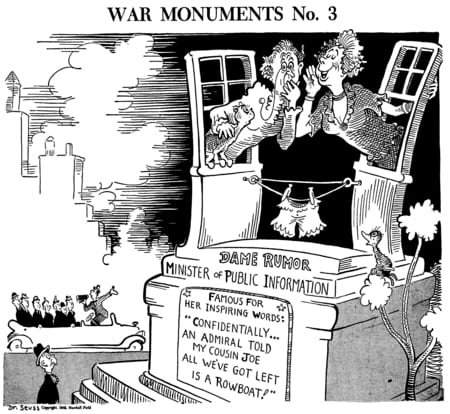

Document B: War Monuments No. 3, published January 8, 1942

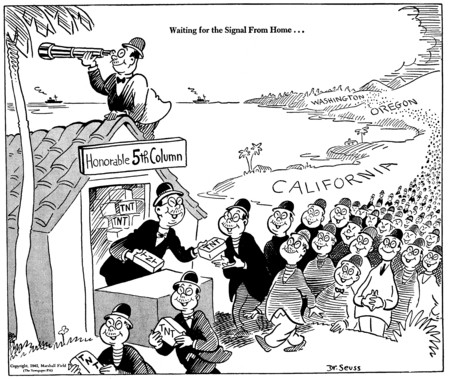

Document C: Waiting for the Signal from Home, published February 13, 1942

Document D: Funny… Some People Never Learn to Keep Their Barn Doors Locked, published February 16, 1942

Lesson Goals: Students should be able to situate the film and the political cartoons on a timeline of World War II events, primarily around the bombing of Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941) and President Roosevelt’s issuance of Executive Order 9066 (February 19, 1942). Students should recognize the difference between making an animated film for enlisted men in the military and drawing political cartoons for the general public. They should also note that the message of the cartoons and the film are quite similar, but the difference in the intended audience has an effect on the context.

Possible extension activity: Compare and contrast Carlos Mencia’s 2002 stand-up routine for Comedy Central Presents with Dr. Seuss’ cartoon “Waiting for the Signal From Home.” What themes emerge?

Reflection: This was a fun project. It seemed to me that it should have been a more difficult task to assemble a lesson on primary sources using a medium that was new to me (Google Presentation), but the Stanford History Education Group’s assessment model was so clear that this lesson came to together almost effortlessly. In fact, it came together so well I thought I must have done it incorrectly, or left something out. My thanks to Sam for thoroughly examining my first draft and offering his insight and support. This is the kind of lesson that makes me feel like I am doing what I am meant to be doing, and moving in the right direction.

Sources:

Document A, Private SNAFU in “Rumors,” is now in the public domain. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZGP7GebzO_E

Document B: War Monuments No. 3, published by PM Magazine on January 8, 1942, Dr. Seuss Collection, MSS 230. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Library. http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dswenttowar/#ark:bb76459366

Document C: Waiting for the signal from home…, published by PM Magazine on February 13, 1942, Dr. Seuss Collection, MSS 230. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Library. http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dswenttowar/#ark:bb5222708w

Document D: Funny… Some people never learn to keep their barn doors locked., published by PM Magazine on February 16, 1942, Dr. Seuss Collection, MSS 230. Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Library. http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dswenttowar/#ark:bb5700525j

American Adobo: The Fight for the Philippines

Lesson design by Samuel Kimerling

Eighth grade students will be asked to evaluate the evidence of historical documents as a means of deepening their understanding of the Philippine War. They will use the historical thinking skills of sourcing, corroboration, and contextualization.

photos credit: US Dept of State Office of the Historian

Directions:

Use the document below and your knowledge of history to answer the questions that follow.

Source:

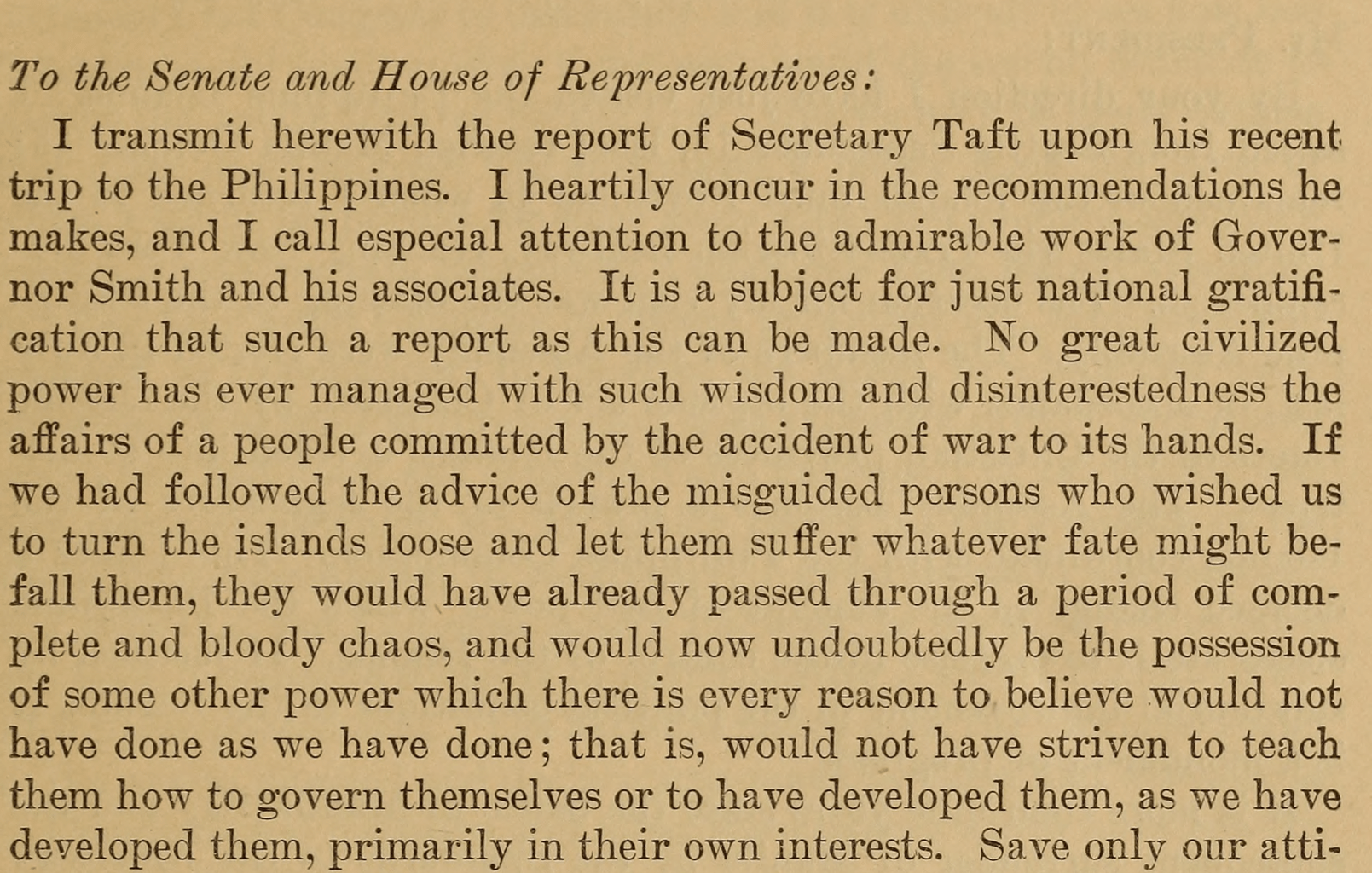

An excerpt from President Theodore Roosevelt’s introduction to a special report by Secretary of War Howard Taft regarding the accomplishments of the U.S. Army in the Philippines from 1898-1908.

photo credit: Library of Congress

Source text (excerpt):

“It is a subject for just national gratification that such a report as this can be made. No great civilized power has ever managed with such wisdom and disinterestedness the affairs of a people committed by the accident of war to its hands. If we had followed the advice of the misguided persons who wished us to turn the islands loose and let them suffer whatever fate might befall them, they would have already passed through a period of complete and bloody chaos, and would now undoubtedly be the possession of some other power which there is every reason to believe would not have done as we have done; that is, would not have striven to teach them how to govern themselves or to have developed them, as we have developed them, primarily in their own interests.”

Question 1: Explain why a historian might question why Roosevelt’s praise for the military outcome in the Philippines may not be a “subject of just national gratification”?

Students will need to understand that there was major debate over imperialism during this time. Students will use the skills of sourcing and contextualization.

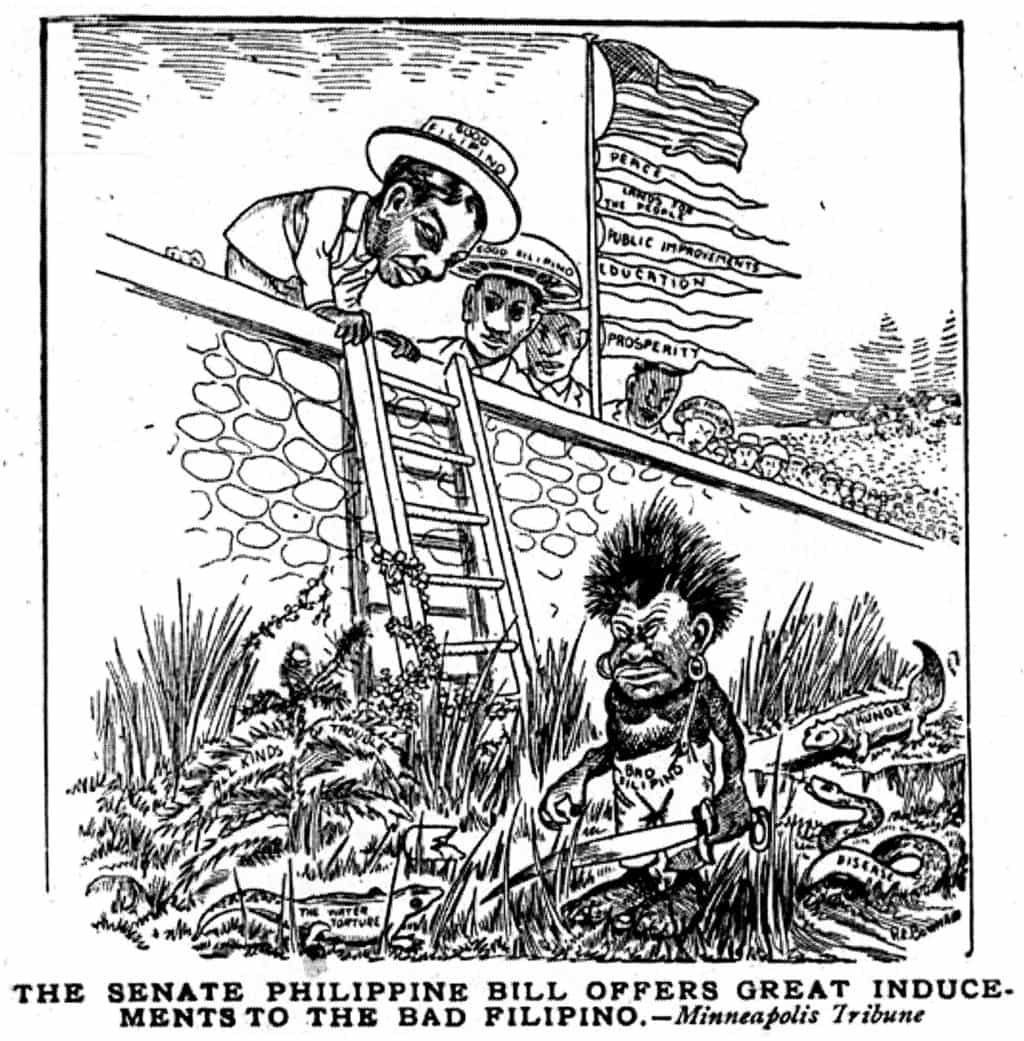

Question 2: Three documents are listed below. Explain whether each document supports or conflicts with the President’s view on the military success of the Philippine War.

Students will see the various facets of the for and anti-imperialist sentiment. Students will use skills of sourcing and corroboration.

a. 1901 Petition to the Senate and House of Representatives from the Philanthropic Committee of the Religious Society of Friends which advocates for making peace with the Filipino insurgents and granting their independence.

Source text (excerpt): “The Filipino people, we feel, have a right to look to this Republic not only as an example of free government, but for effective aid and support in the establishment and maintenance of institutions of their own, freely chosen by them, and adapted, in their judgement, to their circumstances and conditions. This the American people long ago claimed for themselves, and have never heretofore denied to others.”

photo credit: Society of Friends

b. Mark Twain’s essay, “To the Person Sitting in Darkness,” delivered to the New York Anti-Imperialist League in 1901.

Source text (excerpt):“True we have crushed a deceived and confiding people; we have turned against the weak and the friendless who trusted us; we have stamped out a just and intelligent and well-ordered republic; we have stabbed an ally in the back and slapped the face of a guest; we have bought a Shadow from an enemy that hadn’t it to sell; we have robbed a trusting friend of his land and his liberty…”

Published May 5, 1902 New York Journal “Kill Everyone Over Ten-Criminals Because They Were Born Ten Years Before We Took The Philippines”

c. Republican Senator Albert Beveridge’s “March of the Flag” campaign speech of September 16,1898.

“The Opposition tells us that we ought not to govern a people without their consent. I answer, The rule of liberty that all just government derives its authority from the consent of the governed, applies only to those who are capable of self-government. We govern the Indians without their consent, we govern our territories without their consent, we govern our children without their consent. How do they know that our government would be without their consent? Would not the people of the Philippines prefer the just, humane, civilizing government of this Republic to the savage, bloody rule of pillage and extortion from which we have rescued them?”

Minneapolis Tribune 1902

photo credit: Philippines 1900

Self Reflection

This project challenged us to design a lesson that encouraged students to think like a historian. Designing a lesson like this proved challenging to me as I am used to simply conveying information in a lesson. This model relies less on the transfer of information and more on the thought process. It was helpful to have the SHEG resources as a scaffold to help figure out what a good lesson looked like. I ended up spending a lot of time searching for primary sources and trying to figure out the best way to make them fit together to make a coherent question set. By the time I was done searching I had discovered and bookmarked some great sources for original documents. I would definitely give this type of project a try in the classroom, as I think making the student the historian is key to getting them to understand why history is important, and why we study it in school. Historical thinking is critical thinking which can be applied across disciplines and prove useful in life outside the classroom. Moving the classroom experience away from the transfer of information, and towards the acquisition of thinking skills, not only engages the student more, but prepares them better for the future.