Advice to Future Self on Undertaking a DBQ Project:

- Start with the document(s) first. Learn about it (or them), and place that document in a time period and look at everything that surrounds it. Follow the rabbit trail from MLK’s “Beyond Vietnam” to Langston Hughes’ “Let America Be America Again” and see where it takes you. The themes will show themselves sooner or later. Humans are programmed to seek out patterns and find the stories. But starting with a theme and hoping to find documents to undergird that theme is risky. It could work, but it could also lead you on a search for something that doesn’t exist.

- Be careful about trusting your crazy brain. Sometimes it does magic tricks when you least expect it. Sometimes it lets you think it can do the impossible. This is when you need to reach out to, and listen to, the friends who will be bluntly honest with you and tell you when you’re headed out onto unfruitful waters.

- Don’t try to answer philosophical questions with a DBQ project. Yes, there is an inherent discrepancy between perception and reality. Great. But a DBQ is probably not the correct avenue to explore such an idea. However, don’t be afraid to present the unanswerable questions. Part of life is learning that not all questions have answers.

- If you know how your brain works best, go with it. I tried to learn how to design a DBQ while simultaneously trying to figure out how to use Learnist and Evernote with my brain balking at me all the way. When I finally relented to how I learn best (paper and Pilot G-2 pen), my brain finally began to kick into gear. If I had accepted the truth of how my brain works sooner, I could have just gotten the work done and copied and pasted my work into these new programs afterwards. Trying to learn a design process while attempting to learn a new computer program was too taxing and, ultimately, unproductive.

- Don’t let your heart get broken, don’t lose anyone you love, and don’t get ill. These will all interfere with your work.

- Don’t be afraid to suck at something the first time you try it. Scarred knees are simply reminders that you now know how to ride a bicycle. Embrace the suck. Listen to Samuel Beckett: “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

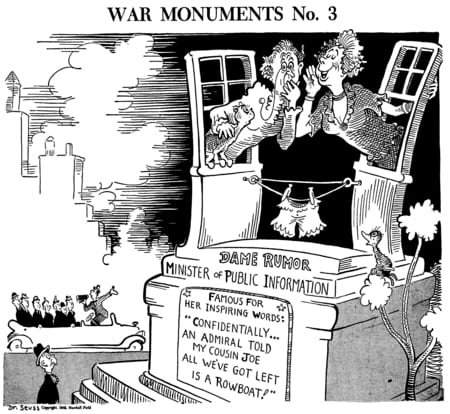

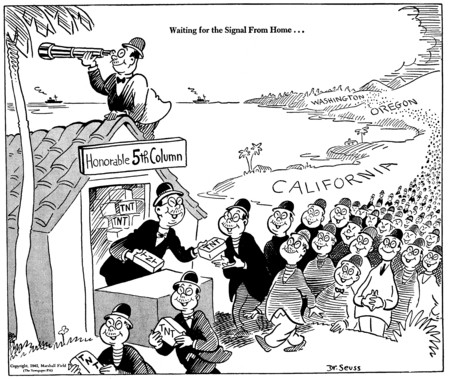

Image credit: Private collection of Karen Elaine Parton