Gaining new perspectives and going new places in a time of isolation

About this time last year my wife and I dragged our tired kids from their naps, got them changed, and packed the car. We put in water bottles, enough snacks for a weekend backpacking trip, and cozy hats, gloves, and scarves. A short 20 minute drive later (full of music from Amy Grant’s incredible 90s Christmas album) we arrived at the Portland Zoo for their annual Zoo lights. It was a noisy affair, jostling and bumping into strangers as we waded through the crowds to find the next display. We sat in the old train as it drove through the zoo, all the while my son spilled hot cocoa on his jacket because he couldn’t keep his eyes off the lights.

Looking back, this all feels very odd. Crowds. People. Noise. No masks to be seen, except those used to keep faces warm. This year has taken much from us, and asked of us even more. Now a student teacher, I’ve seen first-hand the toll that distance learning has taken on students and parents alike. As teachers, what can we do to use our subjects not only as vehicles for learning, but also as ways for kids to experience wonder, excitement, and enjoyment of new things in a time when they are primarily stuck in home?

Make history come alive

Now we have a real chance to change hearts and minds when it comes to a subject that can often be dry and repetitive. History (and Social Studies) can be an escape from the ordinary, and an opportunity for adventure for students who are otherwise sitting in their living rooms. When airports are closed, hotels are dangerous, and travel is expensive, a history lesson can still transport students somewhere new. My hope through these activities is that students can still experience at least a little of what it would be like to really be somewhere…to be anywhere. Use history as a tool for learning and exploring…maybe even a short respite from the monotony of isolation. I’ve highlighted a few lessons here that I hope could do this.

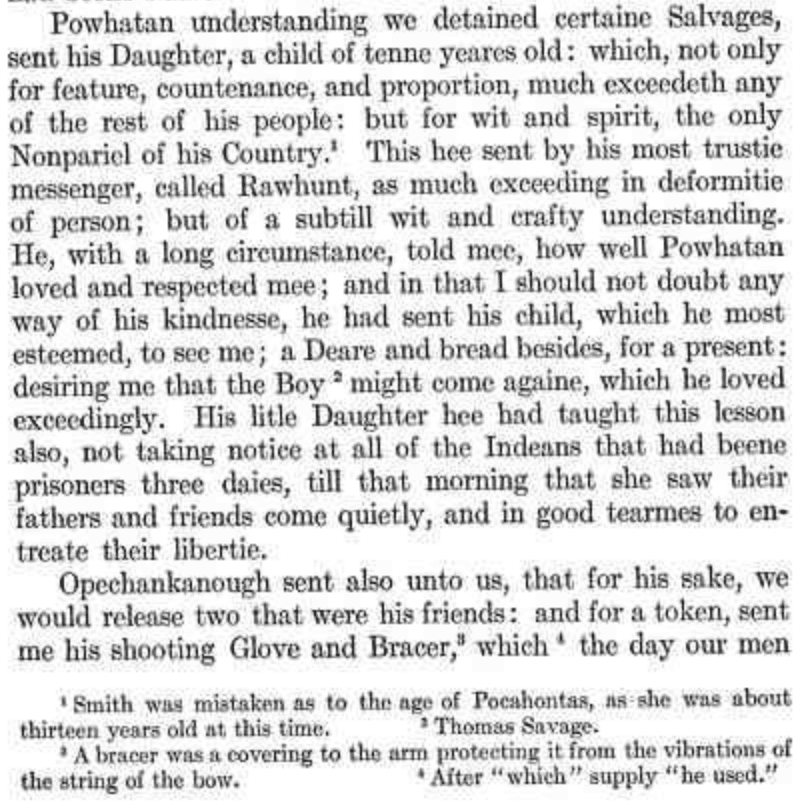

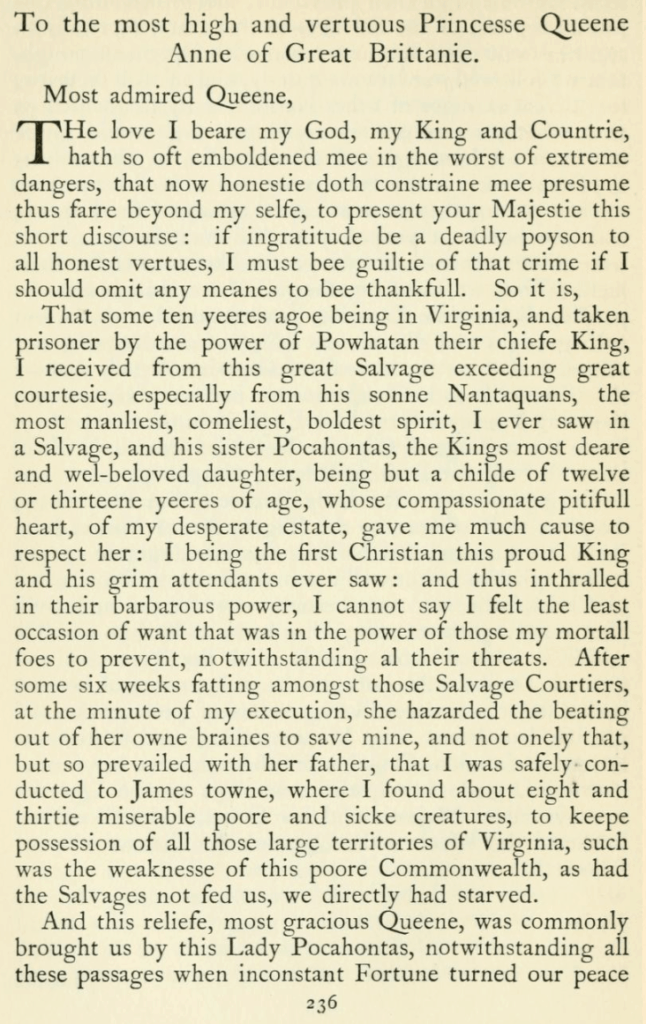

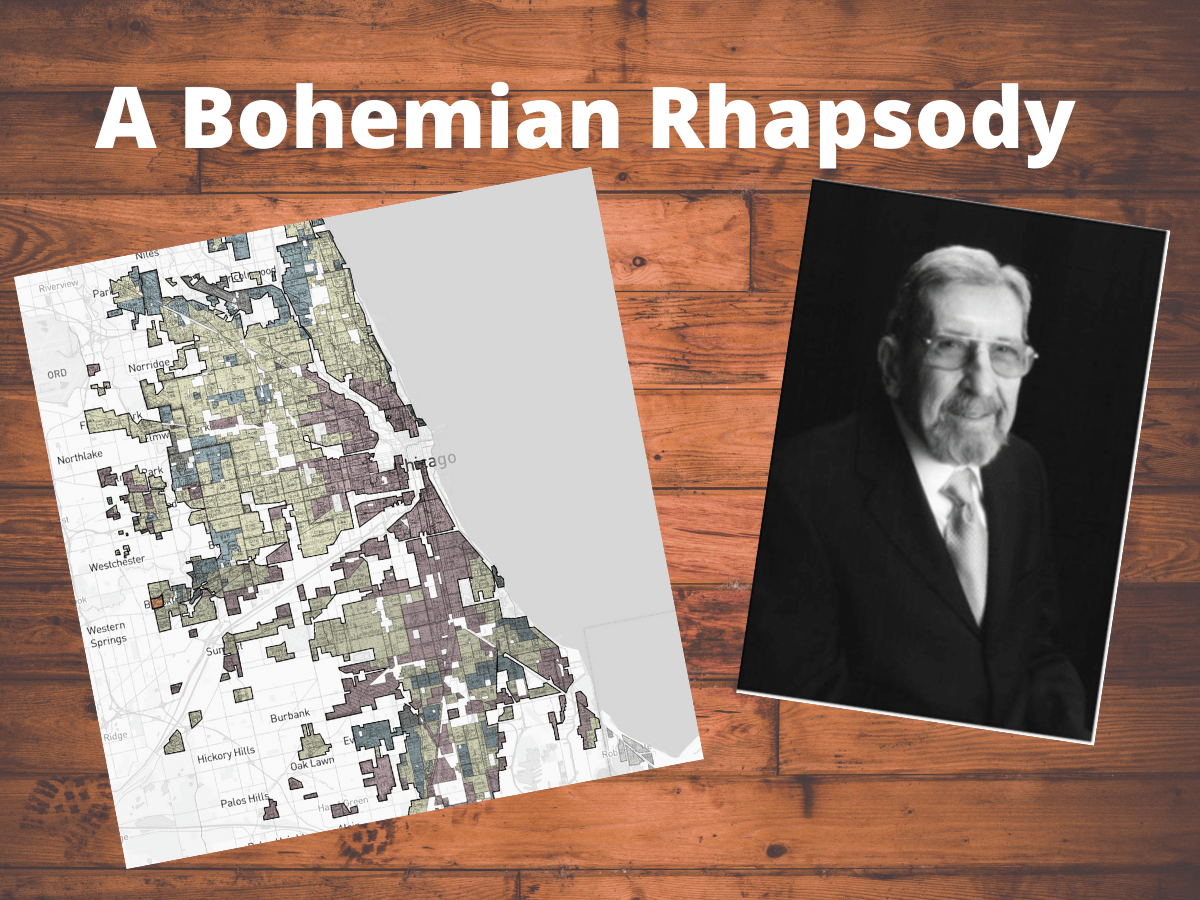

The Lessons

Here I examine the exploration of the city of Barcelona through comparative images and maps. We used a picture compare to show side-by-side changes over time between old Barcelona and today. In this way I hope to not only give students a glimpse of the past and an opportunity to talk about change, but to also allow them to explore on their own. We are able to use these images to place ourselves in a space and time, to transport via our imaginations. The very process of examining the map can be an escape as well as an opportunity to critically think about what societies value and how they change over time.

The next lesson I’ve highlighted is a lesson I designed around using travelogues as primary sources. In it we examined excerpts from two travelogues written by Muslims as they journeyed in and around the Middle East, Indian Ocean, and India. The goal with this lesson is to critically evaluate how to use travelogues as primary sources by considering what kind of information is or is not reliable, and examining author intents. I feel like this lesson also allows for a lot of freedom from the teacher to let students get lost in the experiences of another. Learning empathy by better understanding another culture, as well as the simple idea of using your imagination to place yourself somewhere new…these are valuable skills that desperately need attention in these times.

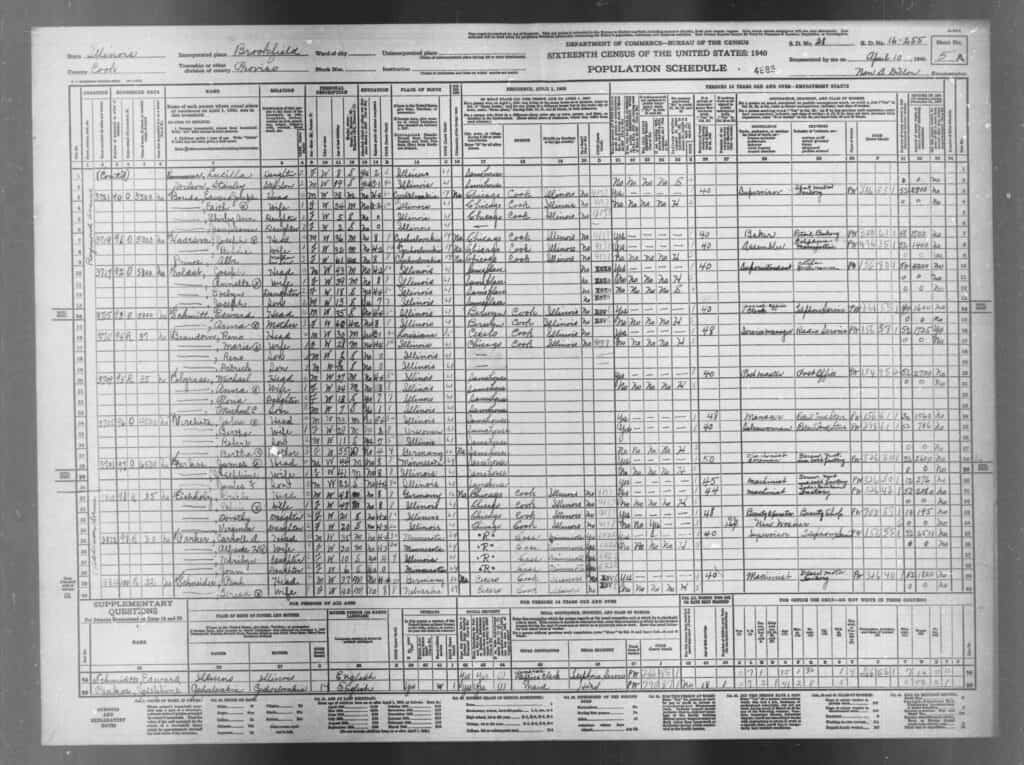

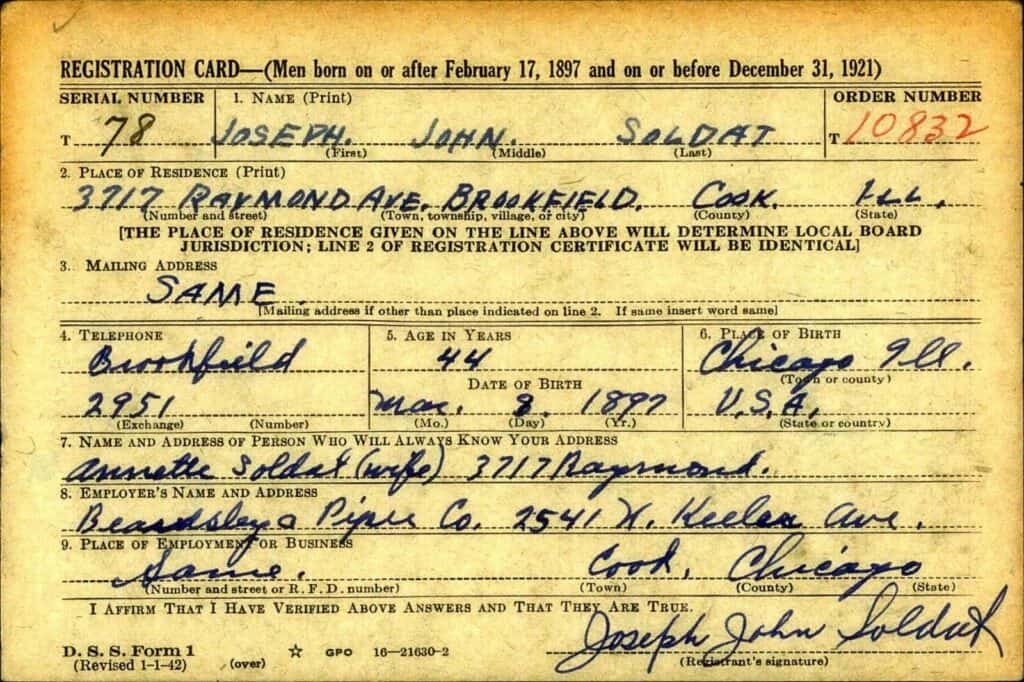

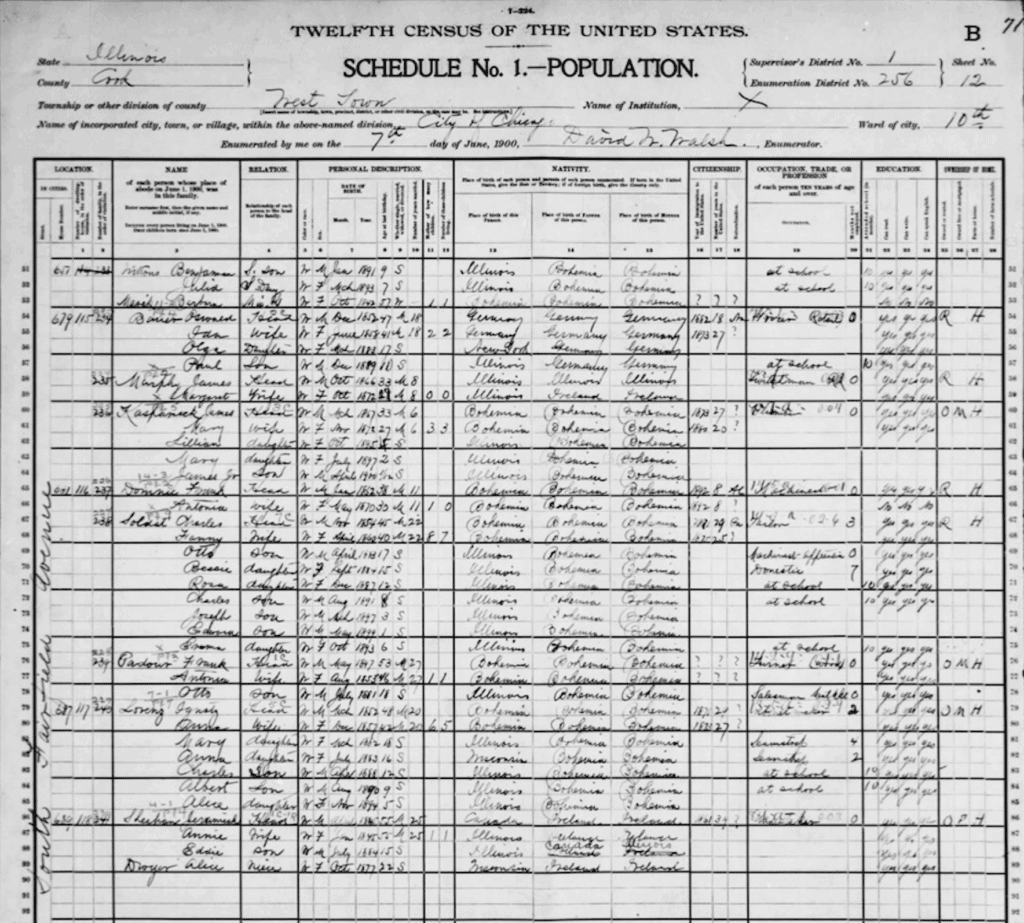

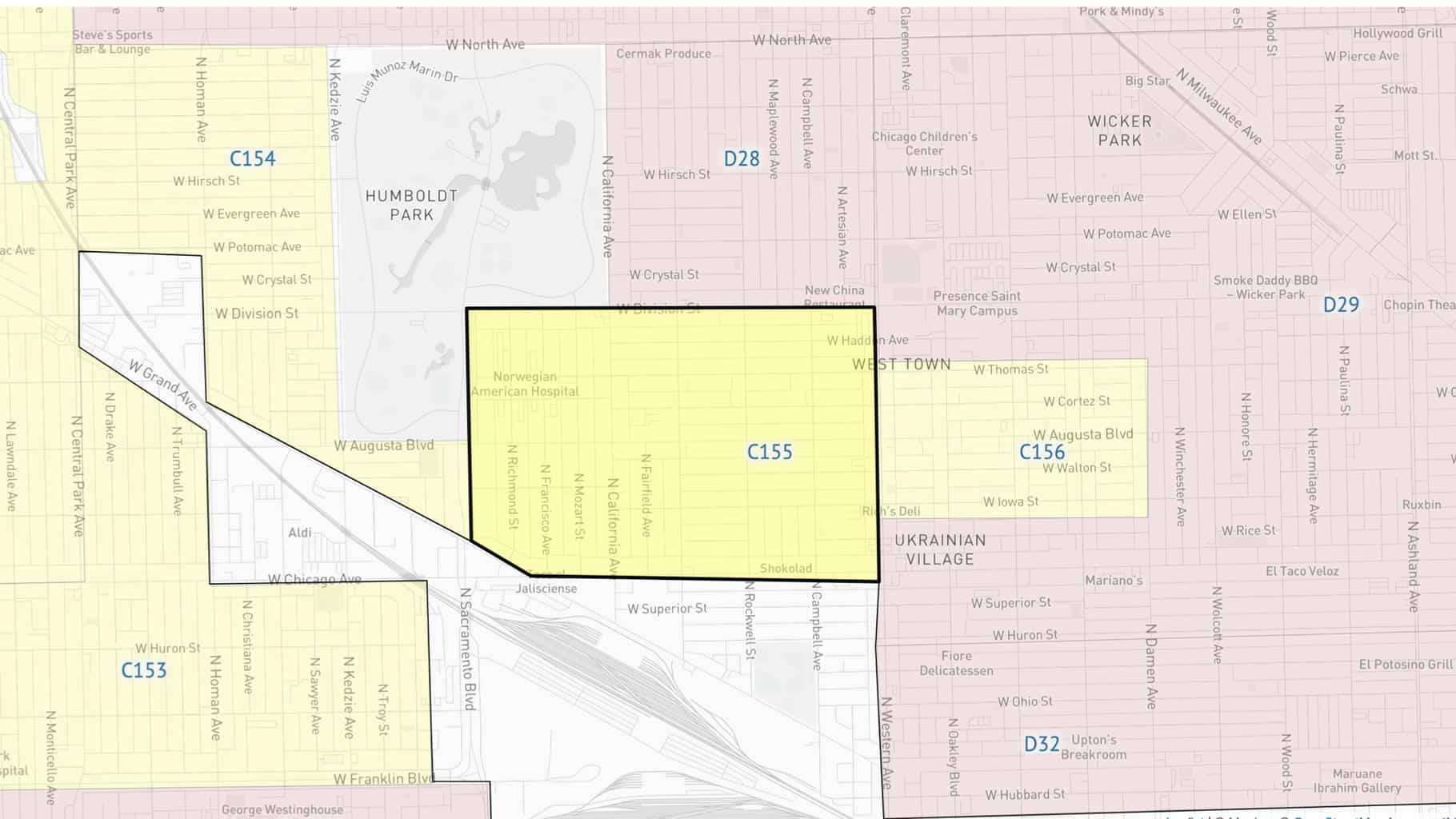

While this was certainly a more personal type of post, the lesson itself was a great way to really lose yourself in another person’s experiences. We examined census data and maps to look at the real living situations and historical livelihoods of relatives, friends, or even complete strangers. This was a great way to learn about new places, and could be a personal journey for some students who may be cut off from their family during distance learning and a pandemic. I look for assignments to create experiences for others that not only teaches them, but also engages them emotionally.