Description:

This lesson will go over propaganda in World War I, particularly propaganda targeting Germany. In any war, propaganda is made to instill a hatred of the enemy in the general populace and thereby motivate them to participate in the war in a number of ways from buying war bonds, to helping build weapons and vehicles, to actually serving on the battlefield itself. This lesson will go over propaganda from WWI and how it demonizes the enemy in a number of ways to truly make them the “enemy”. The class will be divided into groups and exam each work and discuss within their groups as to what they see and how it depicts the enemy. The class will then return together and have a class discussion on each work. The aim of this lesson will be for students to observe and analyze the works of propaganda and use this as a framework to build upon prior knowledge of the unit that concerns WWI itself. Ideally, this lesson would come in the middle of the unit so that the students have prior knowledge to draw up to make connections with the propaganda pieces. This lesson will primarily be focused on the contextualization aspect and will revolve around the students bringing context into their analysis of the propaganda

Sources

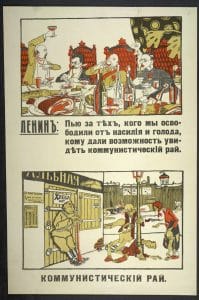

What does this image portray Germany as? What in particular stands out?

What does this portrayal tell us about the creators view on the Germans? Why portray Germany in this way?

Why portray a German solider as an ape?

Who is the damsel in distress supposed to be?

What does this tell us about the creators view of the Germans?

What do the words on his helmet and club refer to?

Reflection

I think that a lesson on propaganda alone in the modern era would be a very interesting and insightful topic since it acts as a lens through which to view the past. Propaganda is often very crude and vulgar in the portrayals of the enemy and this reveals a lot about what was thought of the enemy at the time but also can reveal other underlying issues such as gender (featured with the damsel in distress in picture 2) and often race but this occurs much more frequently in WWII propaganda particularly the propaganda concerning the Japanese. This would certainly reinforce the students understanding of the times and offer insight as to the thinking of the time, both about the war and even on other issues that the propaganda did not directly set out to address. Overall, I think this lesson would be very beneficial to students and their understanding of the war and the mentality that surrounded it.

Works Cited

Photo 1

William Allen Rodgers, Only The Navy Can Stop This, 1917 https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2001700444/

Photo 2

Harry R. Hopps, Destroy This Mad Brute, 1917 http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/ds.03216/